|

Exercise For Diabetes Mellitus

Author:

Stan Reents, PharmD

Original Posting:

08/02/2007 10:33 AM

Last Revision: 08/22/2019 02:42 PM

As of 2015, diabetes, or more specifically, diabetes mellitus, is listed as the 7th leading cause of death in the US. Quite frankly, diabetes is out of control, both in the US, and worldwide. Consider the following statistics:

DIABETES IN THE US

The prevalence of diabetes in the US gets worse every year:

| YEAR |

PREVALENCE

OF DIABETES

IN THE US |

| 2005 |

20.8 million |

| 2010 |

25.8 million |

| 2012 |

29.1 million |

| 2015 |

30.3 million |

Of the 30.3 million Americans (all ages) with diabetes, 23.1 million are diagnosed while 7.2 million are not officially diagnosed (source: NHANES data obtained 2011-2014).

30.3 million people represents 9.4% of the total US population. But an additional 84.1 million adults have pre-diabetes! These are people with an elevated blood glucose between 100-125 mg/dL. Most will go on to develop full-blown diabetes. As I've been saying, diabetes is going to get a lot worse before it gets better.

| CATEGORY |

FASTING

BLOOD GLUCOSE |

PREVALENCE

(US adults only,

2015) |

| • Diabetes Mellitus |

> 125 mg% |

• With diagnosed

diabetes: 22.8 million

(9.2% of adults) |

| • Pre-Diabetes |

100 - 125 mg% |

84 million

(33.9% of adults) |

• Diabetes in adults (ages 18 and above): If you add up adults who currently have diabetes (22.8 million) and adults with pre-diabetes (84.1 million), there are 107 million adults at risk. That's more than 40% of all adults in the US!

• Diabetes in children and adolescents: Because of its association with obesity and a sedentary lifestyle, type 2 diabetes used to be a disease that was only found in adults. It is now being seen in children and adolescents.

• Diabetes in Native Americans: Most often, the cause of type-2 diabetes is lifestyle (ie., a combination of sedentary lifestyle and overeating, leading to obesity). However, genetic factors also play a role. At least 10 genes involved in the development of diabetes mellitus have been identified in humans. A prime example is the high prevalence of diabetes in Native Americans, particularly Pima Indians. The rate of diabetes in American Indians is the highest of any ethnic group in the US.

DIABETES WORLDWIDE

And if the stats listed above aren't depressing enough, then consider what is going on worldwide:

| YEAR |

WORLDWIDE

PREVALENCE OF

DIABETES |

| 1985 |

30 million |

| 2000 |

150 million |

| 2010 |

285 million |

| 2011 |

366 million |

(source: Diabetes Atlas, 4th ed., published by the International Diabetes Federation)

In the fall of 2011, world population reached 7 billion. So, stated another way, about 5.2% of the entire world population has diabetes mellitus. It is estimated that, in 2011, one person died from diabetes every 7 seconds.

TWO TYPES OF DIABETES

Diabetes exists in 2 general types:

- Type-1: due to reduced output of insulin from the pancreas

- Type-2: insulin output is normal or increased, but responsiveness of tissues to the actions of insulin is impaired (insulin resistance)

Type-2 makes up 90-95% of all cases of diabetes.

OBESITY LEADS TO DIABETES

One of the main reasons for the steady increase in diabetes is because obesity continues to get worse. The most recent stats on obesity in the US (from NHANES) show the following:

- Males: 35% are obese

- Females: 40% are obese

- Adolescents ages 12-16: 21% are obese

Obesity, particularly if it occurs at an early age, is a strong risk factor for developing diabetes in later life. At the American Diabetes Association meeting in Washington DC (June 12, 2006), Dr. Venkat Narayan, head of epidemiology and statistics at the CDC's diabetes branch, presented a report based on survey data from over 800,000 healthy adults. He found that:

...the odds that a person who is a normal weight at age 18 yrs. will develop diabetes in later life are roughly 1-in-5, or 1-in-6. This is bad enough. But, "if you are very obese at age 18, the risk of developing diabetes rises to 3-in-4," he said.

Combined data from the Nurses' Health Study (77,690 women) and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study (46,060 men) also show how the risk of diabetes skyrockets as body weight increases (Field AE, et al. 2001):

| BMI |

INCREASED RISK

OF DIABETES |

| 25 - 29 |

4.6-fold increase |

| 30 - 34 |

10-fold increase |

| 35 and higher |

17-fold increase |

Even professional athletes are not immune to the consequences of weight gain and a sedentary lifestyle. NBA hall of famer Dominique Wilkins discovered that first-hand. After he retired from the NBA, he put on about 25 pounds, and then was diagnosed with type-2 diabetes. He has since lost about 30 pounds, improved his diet, and resumed a more disciplined exercise routine, but still requires oral medication to control his diabetes. (His father suffered from type-1 diabetes.)

Prevent Obesity by Controlling Your Calorie Intake

As summarized above, obesity is a major risk factor for type-2 diabetes. Preventing weight gain is a lot easier than dieting to lose excess weight.

Americans obtain one-third of their calories outside the home. And, as we all know, restaurant portions are huge. Research shows that the more often people eat at restaurants, the more likely they are to gain weight.

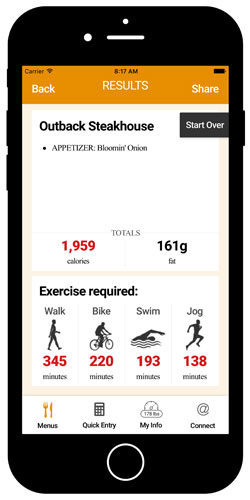

To help you make smarter choices when dining out, use our novel and award-winning Exercise Calorie Converter mobile app. Not only can you look up the calorie values of over 6000 menu items from more than 50 franchise restaurants, you can quickly convert those calories into minutes of exercise. Thinking of calories in this manner really emphasizes the importance of preventing weight gain!

"TREATING" DIABETES WITH EXERCISE

People with diabetes know how important diet is to maintain good blood sugar control. But, fewer are clear on how beneficial exercise can be.

This is not surprising. Healthcare professionals often recommend "diet and exercise" for patients with diabetes. But, while the details regarding diet are clearly spelled out for diabetics, specific information regarding exercise is not. How much exercise? How often? And what type?

In 1972, Paula Harper, a registered nurse, was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes. She discovered that the medical profession offered very little help when she asked these questions. In fact, she says, "I was most often told not to do it or given inadequate or misleading advice." She subsequently developed her own training regimen and, within a year, entered her first marathon. She has since run dozens of marathons, and competed in other endurance races, such as triathlons, ultramarathons, and century bike races (Thurm U, et al. 1992).

Sadly, for a long time, the medical profession continued to discourage diabetic athletes from competition. In 1999, American swimmer Gary Hall Jr. was diagnosed with diabetes. His doctor told him he wouldn't swim competitively. Fortunately, Hall didn't listen: At the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens, Hall won the men's 50-meter freestyle, earning him the title "World's Fastest Swimmer!"

In fact, for many people with type-2 diabetes, regular exercise can be highly effective.

Mike Huckabee Reverses Diabetes with Diet and Exercise

Former Arkansas governor Mike Huckabee is an example of someone who developed type 2 diabetes as a complication of obesity:

In 2003, Governor Huckabee weighed 280 lbs. His BMI was 39, one unit shy of being categorized as "morbidly obese." At his height (5'11"), his weight should be no greater than 175 lbs (based on desirable BMI values).

Then, one day in March 2003, Huckabee developed numbness and tingling in his arm. His physician diagnosed diabetes.

The call to action for Mike Huckabee came in June 2003 when former Arkansas governor Frank White died of a heart attack. Over the next year, Huckabee changed his diet and began running. First, he reduced his intake from 3000 down to 800 calories per day by eating meal replacement shakes and unlimited vegetables. After 3 months, his physician relaxed the diet to 1600 calories per day.

After he lost 40 lbs., exercise was added. Though tough at first, after 4 months, Huckabee could run 3-4 miles. By March 2004, he had lost 105 lbs. and all symptoms of diabetes had been reversed.

Huckabee was profiled in Runner's World magazine. He ran his first 5-K race on July 4, 2004 and finished in 28:39 minutes. As of November 2006, he had run 3 marathons and was planning to run in the NYC Marathon. At the Little Rock Marathon in March 2006, his finish time was 4:26.

PHYSIOLOGIC ACTIONS OF EXERCISE IN DIABETES

To better understand the effects of exercise on glucose control, we need to separate this process into two parts: (a) the acute effects of exercise (ie., what happens during an exercise session and for several hours afterwards) and (b) the chronic effects of exercise (ie., what happens when you exercise regularly week after week). The following information is from the excellent text: Action Plan For Diabetes, by Darryl E. Barnes, MD.

Immediate Effects of Exercise

During exercise, muscles use glycogen (the storage form of glucose in muscle) for energy. When glycogen is depleted, the muscle restores this loss by taking glucose out of the blood. Insulin plays a key role in controlling glucose transport into cells.

Exercise stimulates cells to become more sensitive to insulin. This allows glucose to be transported into the cells at a faster rate and, in turn, reduces the blood glucose level.

But, in type-1 diabetes, there isn't enough insulin.

Fortunately, during exercise, muscle cells take up glucose even if insulin is not present. Thus, exercise is highly beneficial for diabetics in 2 ways:

- exercise increases insulin sensitivity

- exercise increases glucose uptake (into muscle cells) independently of insulin

Both of these processes help to lower the blood glucose level. The process is the same for diabetics and non-diabetics. In fact, the effects of exercise can be so effective that in some non-diabetics, aerobic exercise can even reduce blood glucose levels below the normal range (70-100 mg%) (Felig P, et al. 1982).

Long-term Effects of Exercise

The chronic effects of exercise are related to the increase in metabolically active muscle. Regular exercise over time produces more active muscles, which in turn use more glucose, keeping the blood level in control. Improvements in glucose metabolism can be seen within one week of starting aerobic activities. However, if you stop exercising, these effects can be reversed in as few as two days.

The benefits of regular exercise in diabetes are several:

• Improvements in glycosylated hemoglobin: Glycosylated hemoglobin, or hemoglobin A1c (HgA1c), shows the impact of glucose levels over the previous three-month period. People with type-1 diabetes experience positive effects from exercise similar to those experienced by people with type-2 diabetes. However, in those with type-1 diabetes, the changes in HgA1c are entirely dependent on insulin doses and diet.

• Improved circulation: Microscopically, a muscle that has been exercised regularly has an increase in the number of very small vessels (called capillaries) compared to a muscle that has not been exercised. An increase in capillary density allows more blood flow to active muscle which, in turn, increases the efficiency of glucose metabolism.

• Weight loss: Weight loss is a common result of exercise in a person with type-2 diabetes. Typically weight loss will improve the overall health of someone with type-2 diabetes and will decrease the need for insulin in those who are dependent on it. However, a review of 14 studies on the effects of exercise in diabetics showed that exercise improves glycemic control even if no weight is lost (Boule NG, et al. 2001).

Thus, the effects of aerobic exercise on glucose/glycogen metabolism are very therapeutic in diabetics.

OFFICIAL EXERCISE RECOMMENDATIONS FOR DIABETICS

So, this brings us back to the original questions: What kind of exercise is recommended for diabetics? Is aerobic exercise better than resistance exercise? And how much exercise is necessary? How often? How intense?

Official exercise recommendations for diabetics come from the American Diabetes Association (ADA), and from the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). In 2000, the ACSM published a position statement recommending exercise for people with diabetes. This was followed in 2002 by similar recommendations from the ADA (note that the recommendations pertain specifically to type-2 diabetes):

All adults with type 2 diabetes should obtain at least 150 minutes

of exercise or physical activity each week.

This works out to roughly 30 minutes per day, 5 days per week.

AEROBIC EXERCISE FOR DIABETES: DURATION vs. INTENSITY

The official guidelines listed above state how long to exercise, but not how hard, or what kinds of exercise are best.

In terms of mortality, a study from the CDC concluded that 2 hours of walking per week lowered the mortality rate in adults with diabetes by 39%. Mortality rates were even lower for those who walked 3-4 hours per week. The researchers calculated that one death per year could be prevented for every 61 people who walk at least 2 hrs/week (Gregg EW, et al. 2003).

Since then, official exercise recommendations have been refined somewhat. How LONG to exercise depends on how HARD you exercise:

|

MODERATE INTENSITY

AEROBIC EXERCISE |

VIGOROUS INTENSITY

AEROBIC EXERCISE |

| • How long? |

150 min/week |

75 min/week |

| • Examples: |

brisk walking |

jogging, tennis |

In a thorough review, John Ivy, PhD at the University of Texas at Austin concluded that resistance exercise improves insulin sensitivity to about the same extent as aerobic exercise (Ivy JL. 1997). Hemoglobin A1c was lower in diabetics who exercised regularly. It didn't make any difference whether exercise was aerobic exercise or resistance exercise (Boule NG, et al. 2001). However, for reasons discussed below, aerobic exercise is generally preferable than resistance exercise for diabetics.

RESISTANCE EXERCISE FOR DIABETES

Research shows that 6 months of resistance exercise improves insulin action in older adults, both males and females (Ryan AS, et al. 2001). However, there are some additional issues to consider when diabetics engage in resistance exercise: Weight-lifting (by anyone) can momentarily drive blood pressure up to astronomical levels. In one report, the brachial artery pressure in a weight-lifter during leg press hit 480/350 mmHg (MacDougall JP, et al. 1985).

One of the complications of diabetes is a change in blood vessels. A concern in diabetics is that such high pressures may damage the tiny vessels of the retina. Peter A. Farrell, PhD, Department of Exercise Science at East Carolina University, writing in a Gatorade Sports Science Institute publication in 2003 states: "Until resistance exercise is proven harmless, the person with diabetes who has preexisting retinal damage should avoid this type of exercise."

SPECIAL GUIDELINES FOR DIABETICS WHO EXERCISE

First, as with any person who is over 40, obtain clearance from your physician before starting a new exercise program, especially if you are out of shape. This may include a stress test. Baseline hemoglobin A1c level should be measured.

The best time of day for diabetics to exercise is in the morning; disturbances in blood glucose are less likely if exercise occurs before breakfast and before the morning dose of insulin (Farrell PA. 2003). Since blood glucose levels can change rapidly, check blood glucose both before and after exercising.

Peter Farrell, PhD, offers these guidelines:

- If blood glucose is < 5 mM (90 mg/dl), consuming some carbohydrates before exercising will likely be needed.

- If blood glucose is 5-15 mM (90-270 mg/dl), extra carbohydrate may not be required.

- If blood glucose is > 15 mM (270 mg/dl), delay exercise and measure urine ketones. If urine ketones are negative, exercise can be performed; no additional carbohydrates are necessary. If urine ketones are positive, administer insulin, and delay exercise until ketones become negative.

Regarding aerobic exercise, monitor RPE (ratings of perceived exertion) instead of exercise heart rate. Diabetes affects nerve conduction. The presence of neuropathy may affect the relationship between exercise intensity and exercise heart rate.

Sports like football and track and field, because activity is intermittent over a prolonged period of time, make it more difficult to balance food intake and insulin doses. Stop exercising immediately if you begin to feel nauseated or confused.

An important recommendation for diabetics is to wear thick socks and properly fitting shoes when exercising. Diabetics may not sense when a blister is forming and this could predispose them to infections.

If you are a diabetic with documented ophthalmic complications of diabetes, resistance exercises and any heavy-lifting activities are discouraged.

PREVENTING DIABETES WITH EXERCISE

So, it's clear that exercise is good for people with diabetes. The obvious next question becomes: Can the risk of developing diabetes be reduced by exercising regularly? And, the answer is, "yes" though genetics may influence this (Laaksonen DE, et al. 2007).

• Research from one randomized trial showed that 150 minutes of physical activity per week, combined with weight-loss of 5-7%, reduced the rate of progression from pre-diabetes (aka: impaired glucose tolerance) to diabetes by 58% (Sigal RJ, et al. 2006).

• Results from the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study also showed a dramatic decrease in the risk of developing type-2 diabetes in adults with existing glucose intolerance. In this study, changes in lifestyle included not only more physical activity, but, also, weight loss, and dietary changes (Lindstrom J, et al. 2006).

• A study from the Harvard School of Public Health, published in 1999, analyzed whether walking pace made any difference in the risk of developing diabetes. This study was conducted in over 70,000 female nurses, ages 40-65, who did not have diabetes. The researchers found that faster walking was better than moderate walking, and, moderate walking was better than slow walking (Hu FB, et al. 1999).

And, there's also evidence that participation in college sports reduces the risk later in life (Frisch RE, et al. 1986). Several explanations could account for this, but it certainly argues for the long-term health benefits of sports and exercise.

QUESTIONS

Q: You've said that regular exercise is important for the health of diabetics. But, can I still be competitive at an elite level if I have diabetes?

ANSWER: The short answer to this is, yes, you definitely can! Even people with type-1 diabetes can succeed at an elite level:

• Distance Cycling: Cyclist Phil Southerland (USA) was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes when he was just 7 months old. Doctors told his mother that he was unlikely to live past age 25. Phil began cycling competitively at age 12. In 2007, he and his team won the 3000-mile Race Across America. He was 25 years old. He went on to combine his passion for cycling with his desire to raise awareness for diabetes by establishing "Team Type-1", a cycling group for athletes with diabetes. In 2012, Southerland and his group partnered with Novo Nordisk to create "Team Novo Nordisk," a squad of elite world athletes who have diabetes. Currently, the group includes nearly 100 cyclists, runners, and triathletes. Today (2018), Phil is 36 years old.

• Distance Running: Distance runner Missy Foy (USA) was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes at age 33. She went on to become the first athlete with diabetes to qualify for the Olympic Marathon trials. She has since won over 70 races at various distances and holds many course records.

• Ironman Triathlon: David Weingard (USA) was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes at age 36 while training for a survival race. A veteran of races including triathlons, he learned how to manage his diabetes during a race and eventually completed the Escape From Alcatraz Triathlon in San Francisco. He then completed several Ironman triathlons. In 2008, he founded Fit4D to improve healthcare services for diabetics.

• Pro Football: Jay Cutler was the quarterback of the Chicago Bears from 2009 to 2016. He has type-1 diabetes.

• Rowing: Sir Steven Redgrave (UK) won gold medals in rowing at 5 successive Olympic Games from 1984 to 2000. In 1997, at age 35, he was diagnosed with type-2 diabetes.

• Sprint Swimming: Gary Hall Jr. (USA) competed in the 1996, 2000, and 2004 Olympics, winning a total of 10 medals. In 1999, he was diagnosed with type-1 diabetes.

Nevertheless, as mentioned previously, diabetics need to be aware of several issues:

• Neuropathy: Neuropathies are a complication of diabetes. This may affect the heart rate response to exercise, thus making it more difficult to monitor exercise intensity, and, may affect sensations in the feet, increasing the risk of blisters.

• Retinopathy: If there is any evidence of retinal damage, weight-lifting (because of blood pressure increases) and sports/activities such as boxing, football, hockey, karate, and judo (because of contact to the head and face) should be avoided.

Q: You didn't address diet. What nutritional strategies are important?

ANSWER: The focus of this article is on exercise so I intentionally didn't provide much discussion of nutrition. However, here are 2 nutritional strategies that you should keep in mind:

Minimize Your Intake of Sugar (Sucrose) and High-Fructose Corn Syrup

An evaluation of nearly 65,000 women over a period of more than 8 years in the Women's Health Initiative Study revealed that daily consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages substantially increased the risk of diabetes (Huang M, et al. 2017).

Most brands of non-diet soda pop are sweetened with high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS). The HFCS used in solid foods (cookies, hard candies, etc.) is 42% fructose (HFCS-42), while the HFCS used in soft drinks is 55% fructose (HFCS-55). However, researchers at the U. Southern California revealed that the actual amount of fructose in most brands of soda pop averaged 59-60%, with some brands containing 65% fructose (Ventura EE, et al. 2011) (Walker RW, et al. 2014).

Both table sugar (sucrose) and HFCS are unnatural forms of fructose. Thus, as best as you can, minimize your consumption of sucrose and HFCS. The fructose in raw fruits doesn't cause the same health problems as sugar and HFCS (Meyer BJ, et al. 1971) (DiNicolantonio JJ, et al. 2015).

Minimize Your Intake of Soybean Oil

In 2015, researchers at UC Riverside found that soybean oil was a more potent inducer of obesity and diabetes than even fructose (Deol P, et al. 2015). This finding hasn't yet been widely reported. However, it should be taken very seriously. Soybean oil is the #1 oil in our food supply. As with HFCS, it's a virtual certainty that we consume soybean oil every single day!

SUMMARY

As summarized above, we are facing a global health crisis from the combination of obesity and diabetes. A sedentary lifestyle is a contributing factor in both conditions. While exercise is important for everyone, it is especially important for those who are:obese, have diabetes or pre-diabetes or have a family history of diabetes. Studies show that regular exercise is not only helpful in managing diabetes, but it may also reduce the chances of developing diabetes in these high-risk groups.

So, if you have diabetes, can you exercise? Yes, you can, and, more importantly, you should!

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Web sites:

The American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists maintains the web site Empower Your Health (www.EmpowerYourHealth.org) that offers consumer information on diabetes.

The CDC offers a variety of consumer resources on diabetes. Their "National Diabetes Statistics Report, 2017" is a 20-page PDF that summarizes the most current statistics on diabetes in the US.

The National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP) offers a variety of educational documents on their web site at: www.NDEP.NIH.gov.

For athletes with diabetes: The Diabetes Exercise and Sports Association (DESA) was founded in 1985 by Paula Harper under the name "International Diabetic Athletes Association (IDAA)", but the name was changed in 2000. In 2011, DESA merged with Insulin Independence, a non-profit organization that was founded in 2005. It appears that DESA has now been retired.

Other useful web sites include:

Books:

Weekend warriors and more serious athletes with diabetes may want to read: Diabetic Athlete's Handbook by Sheri Colberg, PhD.

For health care professionals: Both the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) and the American Diabetes Association (ADA) published position statements recommending exercise for people with diabetes. An excellent paper on exercise and diabetes is Sigal, et al. 2006 (see "References" below). The Gatorade Sports Science Institute document, written by Peter Farrell, PhD (listed below in References) is an excellent resource for health care professionals.

Readers may also be interested in:

EXPERT HEALTH and FITNESS COACHING

Stan Reents, PharmD, is available to speak on this and many other exercise-related topics. (Here is a downloadable recording of one of his Health Talks.) He also provides a one-on-one Health Coaching Service. Contact him through the Contact Us page.

REFERENCES

Acton KJ, Burrows NR, Wang J, et al. Diagnosed diabetes among American Indians and Alaska Natives ages < 35 years - United States, 1994-2004. MMWR 2006;55:1201-1203. Abstract

Boule NG, Haddad E, Kenny GP, et al. Effects of exercise on glycemic control and body mass in type 2 diabetes mellitus. JAMA 2001;286:1218-1227. Abstract

Deol P, Evans JR, Dhahbi J, et al. Soybean oil is more obesogenic and diabetogenic than coconut oil and fructose in mouse. PLoS ONE 2015;10(7):e0132672. Abstract

DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Added fructose: A principal driver of type-2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences. Mayo Clin Proc 2015;90:372-381. Abstract

Duncan GE. Prevalence of diabetes and impaired fasting glucose levels among US adolescents: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1999-2002. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2006;160:523-528. Abstract

Eriksson JG. Exercise and the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Sports Med 1999;27:381-391. Abstract

Eriksson KF, Lindgarde F. Prevention of type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus by diet and physical exercise. Diabetologia 1991;34:891-898. Abstract

Farrell PA. Diabetes, exercise and competitive sports. Gatorade Sports Science Institute Sports Science Exchange 2003;16(3):1-6. (no abstract available)

Felig P, Cherif A, Minagawa A, et al. Hypoglycemia during prolonged exercise in normal men. N Engl J Med 1982;306:895-900. Abstract

Field AE, Coakley EH, Must A, et al. Impact of overweight on the risk of developing common chronic diseases during a 10-yr period. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:1581-1586. Abstract

Flegal KM, Kruszon-Moran D, Carroll MD, et al. Trends in obesity among adults in the United States, 2005 to 2014. JAMA 2016;315:2284-2291. Abstract

Frisch RE, Wyshak G, Albright TE, et al. Lower prevalence of diabetes in female former college athletes compared with nonathletes. Diabetes 1986;35:1101-1105. Abstract

Gregg EW, Gerzoff RB, Caspersen CJ, et al. Relationship of walking to mortality among US adults with diabetes. Arch Intern Med 2003;163;1440-1447. Abstract

Hu FB, Sigal RJ, Rich-Edwards JW, et al. Walking compared with vigorous physical activity and risk of type 2 diabetes in women. JAMA 1999;282;1433-1439. Abstract

Huang M, Quddus A, Stinson L, et al. Artificially sweetened beverages, sugar-sweetened beverages, plain water, and incident diabetes mellitus in postmenopausal women: The prospective Women's Health Initiative observational study. Am J Clin Nutr 2017;106:614-622. Abstract

Ivy JL. Role of exercise training in the prevention and treatment of insulin resistance and non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Sports Med 1997;24:321-336. Abstract

Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type-2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med 2002;346:393-403. Abstract

Laaksonen DE, Siitonen N, Lindstrom J, et al. Physical activity, diet, and incident diabetes in relation to an ADRA2B polymorphism. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2007;39:227-232. Abstract

Lindstrom J, Ilanne-Parikka P, Peltonen M, et al. Sustained reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes by lifestyle intervention: follow-up of the Finnish Diabetes Prevention Study. Lancet 2006;368(9548):1673-1679. Abstract

MacDougall JP, Tuxen D, Sale DG, et al. Arterial blood pressure response to heavy resistance exercise. J Appl Physiol 1985;58:785-790. Abstract

Manson JE, Rimm EB, Stampfer MJ, et al. Physical activity and incidence of non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus in women. Lancet 1991;338:774-778. Abstract

Manson JE, Nathan DM, Krolewski AS, et al. A prospective study of exercise and incidence of diabetes among US male physicians. JAMA 1992;268:63-67. Abstract

Meyer RJ, de Bruin EJ, Du Plessis DG, et al. Some biochemical effects of a mainly fruit diet in man. S Afr Med J 1971;45:253-261. Abstract

Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Lawman HG, et al. Trends in obesity prevalence among children and adolescents in the United States, 1988-1994 through 2013-2014. JAMA 2016;315:2292-2299. Abstract

Pan XR, Li GW, Hu YH, et al. Effects of diet & exercise in preventing NIDDM in people with impaired glucose tolerance. Diabetes Care 1997;20:537-544. Abstract

Ryan AS, Hurlbut DE, Lott ME, et al. Insulin action after resistive training in insulin resistant older men and women. J Am Geriatr Soc 2001;49:247-253. Abstract

Sigal RJ, Kenny GP, Wasserman DH, et al. Physical activity/exercise and type 2 diabetes. A consensus statement from the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care 2006;29:1433-1438. Abstract *** Recommended reading for health care professionals ***

Smutok MA, Reece C, Kokkinos PF, et al. Effects of exercise training modality on glucose tolerance in men with abnormal glucose regulation. Int J Sports Med 1994;15:283-289. Abstract

Thurm U, Harper PN. I'm running on insulin. Summary of the history of the International Diabetic Athletes Association. Diabetes Care 1992;15:1811-1813. Abstract

Tuomilehto J, Lindstrom J, Eriksson JG, et al. Prevention of type-2 diabetes mellitus by changes in lifestyle among subjects with impaired glucose tolerance. N Engl J Med 2001;344:1343-1350. Abstract

Ventura EE, Davis JN, Goran MI. Sugar content of popular sweetened beverages based on objective laboratory analysis: Focus on fructose content. Obesity 2011;19:868-874. Abstract

Walker RW, Dumke KA, Goran MI. Fructose content in popular beverages made with and without high-fructose corn syrup. Nutrition 2014;30:928-935. Abstract

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stan Reents, PharmD, is a former healthcare professional. He is a member of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). In the past, he has been certified as a Health Fitness Specialist by ACSM, as a Certified Health Coach by ACE, as a Personal Trainer by ACE, and as a tennis coach by USTA. He is the author of Sport and Exercise Pharmacology (published by Human Kinetics) and has written for Runner's World magazine, Senior Softball USA, Training and Conditioning and other fitness publications.

Browse By Topic:

diabetes, exercise and health, exercise guidelines, exercise information, exercise recommendations, health and fitness targets, sports medicine

Copyright ©2026 AthleteInMe,

LLC. All rights reserved.

|