|

Nutrition Basics: Natural vs. Unnatural Sources of Fructose

Author:

Stan Reents, PharmD

Original Posting:

11/18/2008 07:55 AM

Last Revision: 11/15/2019 07:57 AM

I went to a conference where a dietitian once said: "There are no bad foods, only bad diets."

For the most part, I agree with that statement. However, some nutrients and dietary ingredients deserve special attention because consuming too much of them does indeed lead to health problems. One example is trans fats (also known as partially hydrogenated oils). Fortunately, this man-made ingredient is being phased-out of our food supply.

Another example is fructose when consumed from unnatural (man-made) sources. Here, we're talking about table sugar (sucrose) and corn syrup with boosted amounts of fructose: "high-fructose corn syrup" (HFCS). Because these sweeteners have been added to thousands of processed and ultra-processed foods and beverages, it's likely that we consume sucrose or HFCS every single day.

Research published during the past 10-20 years suggests that consuming excessive amounts of fructose from these unnatural sources is clearly associated with a long list of health problems. In fact, the Center for Science in the Public Interest (CSPI) feels so strongly about the health risks of HFCS that, in 2005, they petitioned the FDA to require warning labels on soda pop.

But how can fructose be bad for us? After all, fructose occurs naturally in honey and many fruits. Raisins, dates, figs, and peaches have some of the highest amounts.

Answer: It turns out that consuming fructose as sugar or HFCS promotes worrisome metabolic and health effects that don't occur after consuming the natural fructose in fruits.

In this review, I'll explain this paradox and summarize some of the research on fructose and its health effects.

BIOCHEMISTRY OF FRUCTOSE

I don't want to make this discussion overly scientific, however, there are several biochemistry details that need to be pointed out.

First, simple sugars are either "monosaccharides" or "disaccharides." Fructose is considered a monosaccharide:

| MONOSACCHARIDES | DISACCHARIDES |

|---|

fructose

galactose

glucose

| lactose

maltose

sucrose

|

From a chemical perspective, fructose truly is unique....even among monosaccharides: glucose and galactose are "aldoses" whereas fructose is a "ketose". This minor, but significant, chemical distinction may explain why fructose's actions on the body are so unique.

Fructose is the sweetest of the natural sugars in the table above. Sucrose (ordinary table sugar) is arbitrarily given a sweetness rating of "100." The sweetness rating of fructose is 170. This explains why honey is so sweet and why even small amounts of high-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) in a food or beverage can make that item taste sweet.

The Amount of Fructose in HFCS Varies

Because (a) fructose is sweeter than sucrose and (b) HFCS is slightly less expensive than sugar, beginning in the 1970s, food manufacturers began increasing the amount of fructose in corn syrup in ever higher concentrations. Then, in 2004, George Bray, MD, and colleagues published a major paper in the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition suggesting a strong association between the increased use of fructose as an added sweetener and the steady rise in obesity in the US (Bray GA, et al. 2004).

This led to a dramatic change in attitude towards the use of HFCS as an added sweetener and it caused many food manufacturers to stop using HFCS and go back to using sugar (sucrose). Do you remember when Coca-Cola made changes like this?

Today, you routinely see packaged foods claiming "No High Fructose Corn Syrup" like the cookie label to the right. But you have to look closely at the Ingredients list below the main Nutrition Facts panel. In this fine print, you will often see some other type of sweetener.

The HFCS used in solid foods like cookies, pastries, and hard candies is 42% fructose, while the HFCS used in soda pop and energy drinks is 55% fructose (see table below).

In 2011 and 2014, Michael Goran, PhD, and colleagues at USC revealed that the fructose content of soda pop ranged 59-61% and stated "several brands appear to be produced with HFCS that is 65% fructose." (Ventura EE, et al. 2011) (Walker RW, et al. 2014) However, a subsequent analysis by another group revealed that the fructose concentration in soda pop was 55% (White JS, et al. 2015).

This most recent study claims their results are more accurate because of the analytical methodology they used.

My opinion? Who cares? Soda pop is something you should completely eliminate from your diet. If you do that, then this hair-splitting research is irrelevant!

Free (unbound) Fructose vs. Bound Fructose

So, the high-fructose corn syrup used in processed and ultra-processed foods contains 42-55% fructose. And sucrose (table sugar) is a combination of [glucose] + [fructose] in a 50:50 ratio. This means that both HFCS and sucrose contain roughly the same amount of fructose.

But the fructose in table sugar is chemically bonded to glucose, whereas the fructose in HFCS is free (unbound). Does this matter?

Years ago, nutrition researchers felt that the "free" fructose (as found in HFCS) was worse for your health than the fructose in sugar (Bray G, et al. 2004a) (Tan D, et al. 2008). Researchers at Rutgers University have reported that a single can of carbonated soda pop contains 5 times the concentration of a specific damaging chemical ("methylglyoxal") than is found in the blood stream of the typical diabetic person (Tan D, et al. 2008). They believe that this molecule is related to the free fructose found in HFCS.

However, Stanhope and colleagues showed that free fructose (eg., HFCS) and bound fructose (eg., sucrose) increased triglycerides to the same degree (Stanhope KL, et al. 2008). So, deciding whether free fructose is worse than bound fructose depends on which health complication you choose to look at.

Today, the general opinion is that sugar (bound fructose) is just as bad for your health as HFCS (unbound fructose). The more important distinction we should focus on is that consuming fructose from sugar and HFCS is much worse for our health than the fructose that occurs naturally in fruits.

SOURCES OF FRUCTOSE

Some dietary sources of fructose are listed below:

| FOOD SOURCE | FRUCTOSE |

|---|

apple juice

HFCS in soda pop

table sugar (sucrose)

HFCS in baked goods

honey

| 65%

55%

50%

42%

38%

|

METABOLIC EFFECTS OF FRUCTOSE

The human body responds to fructose differently than any other mono- or disaccharide. In fact, it can be said that fructose actually disrupts several metabolic pathways (Havel PJ. 2005):

Fructose Impairs the Normal Hormonal Response during Digestion

Normally, when blood glucose goes up, a signal is sent to the pancreas to release insulin. Insulin, in turn, stimulates the release of another hormone: leptin. And leptin suppresses a 3rd hormone: ghrelin. It is thought that this hormonal domino effect is one of the ways the sensation of hunger is suppressed in the brain.

But, when different types of simple sugars were studied, it was found that the hormonal response varied:

• Researchers gave healthy adults an equivalent dose of 3 sugar solutions: (a) 100% glucose, (b) a 50:50 mixture of glucose and fructose, and (c) a 25:75 mixture of glucose and fructose. Insulin output was lower after both glucose:fructose mixtures compared to the 100% glucose solution (Parks EJ, et al. 2008). In other words, fructose did not stimulate insulin output as strongly as glucose did.

Translation: If fructose does not stimulate the "stop eating" signal as readily as other sugars, then, it's possible that people will consume more calories before they feel full.

Fructose Stimulates Lipogenesis (fat synthesis)

Diets that are high in carbohydrates (defined as >55% of energy intake coming from carbs) tend to increase triglyceride levels in the blood (Parks EJ. 2001). This action occurs after consuming refined, starchy carbs as well as after consuming sugar and/or HFCS. But the process of lipogenesis (ie., the synthesis of fat cells) can be as much as 2-fold greater after consuming fructose than after consuming glucose (Krilanovich NJ. 2004) (Parks EJ, et al. 2008) (Stanhope KL, et al. 2008).

Nicholas Krilanovich, writing in the November 2004 issue of the American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, summarizes the effects of fructose as follows:

"...ingestion of large quantities of fructose has profound metabolic consequences because it bypasses the regulatory step catalyzed by phosphofructokinase. This allows fructose to flood the pathways in the liver, leading to enhanced fatty acid synthesis, increased esterification of fatty acids, and increased VLDL secretion, which may raise serum triacylglycerols and ultimately raise LDL cholesterol concentrations."

Translation: Fructose stimulates fat synthesis in the liver and worsens the lipid profile in the bloodstream. Both actions are not good for your health!

Fructose Causes Elevated Uric Acid Levels

Starting in late 2005, nephrologists at the University of Florida began reporting that fructose can increase blood levels of uric acid (Nakagawa T, et al. 2005) (Nakagawa T, et al. 2006). Elevations in uric acid can lead to kidney stones. Then, they reported that fructose -- but not glucose -- accelerated the progression of kidney disease (Gersch MS, et al. 2007). Though, up to this point, all of this research was conducted in rats.

In January 2008, researchers from Harvard documented that fructose consumption increased the incidence of kidney stones in both men and women as well (Taylor EN, et al. 2008).

High uric acid levels are associated with something potentially worse: reduced nitric oxide levels. This, in turn, contributes to insulin resistance and a serious medical condition known as "metabolic syndrome" (see discussion below).

Translation: Fructose has detrimental effects on uric acid, which, in turn, can lead to other health problems.

MEDICAL CONDITIONS RELATED TO FRUCTOSE

So what are the long-term health consequences of these metabolic actions of fructose?

Fructose and Fatty Liver Disease

Fatty liver disease (specifically, "non-alcoholic fatty liver disease") is not a medical condition you hear much about. But, it's more common than you might realize. It's been estimated that 1 out of 4 adults are affected, and some estimate the prevalence is 1 out of 3 adults.

In 2012, researchers from Denmark assigned 47 overweight subjects to 1 of 4 test drinks:

- regular Coke

- diet Coke (sweetened with aspartame)

- skim milk

- noncarbonated water

After 6 weeks, those who consumed regular Coke had accumulated more fat in their liver than the other 3 groups (Maersk M, et al. 2012).

But this was an assessment of soda pop, not just sugar or HFCS.

The following year, an American group performed a somewhat similar study. Instead of studying soda pop, they evaluated the effect of different amounts of sugar or HFCS. They found that when fructose was consumed as part of a normal diet, fatty liver did not develop (Bravo S, et al. 2013).

Why?

First, this study only lasted 10 weeks, so it may have been too short. Second, how researchers evaluated the amount of fat in the liver may explain their differing results.

Then, in 2019, a study appeared in JAMA: 40 adolescent boys (average age 13 years) who had documented fatty liver disease, and, who consumed 3 or more servings of sugar-sweetened beverages (soda pop + juices) per day were randomized to 1 of 2 diets:

- 1% of calories from free sugars

- 10% of calories from free sugars

After 8 weeks, the boys on the lower sugar diet had substantial improvement in their liver health (Schwimmer JB, et al. 2019).

Thus, the implication from these studies is that consuming too much added sugars on a regular basis is definitely a risk factor for developing fatty liver.

Fructose and Obesity

Keep in mind, the research discussed above showing that fructose stimulates fat synthesis is not proof that fructose causes obesity. Weight gain, ultimately, requires consuming more calories than you burn up.

But, if fructose doesn't activate the body's hormonal response in the normal way, isn't it possible that people might eat more than they should?

So, is weight gain and obesity due to eating too many carbs in general, or, is it due to the specific types of carbohydrates in the diet?

Andy Briscoe, president of the Sugar Association in Washington, DC, states:

"Over the last 30 years, the per capita consumption of sugar — sucrose — has gone down from 72 pounds per person to 45 pounds per person a year. If sugar intake has gone down, then it's not as a significant contributing factor to the obesity issue as some people have made it out to be."

The statement from Briscoe above needs to be kept in perspective. While he may be correct that our consumption of table sugar has leveled off, or even decreased, our consumption of HFCS increased between 1980 and 2004.

And so has obesity:

In Dr. Bray's 2004 paper, the incidence of obesity and the consumption of HFCS in the US are plotted together on a graph, a very troubling pattern emerges: There is a noticeable increase in the incidence of obesity in the US starting in the early 1980s (Bray GA, et al. 2004-b).

Statistics don't lie. Several nationwide nutrition surveys show that our daily consumption of fructose (from all sources) has been going up steadily and dramatically:

| NUTRITION SURVEY |

TOTAL FRUCTOSE

CONSUMPTION

(grams per day) |

PERCENT OF FRUCTOSE

FROM WHOLE FRUIT |

1977-1978 USDA

Food Consumption

Survey

(Park YK, et al. 1993) |

• All ages: 37 g/day

• Adolescents: 54 g/day |

(n/a) |

1988-1994

NHANES III

(Vos MB, et al. 2008) |

• Adults: 55 g/day

• Adolescents: 73 g/day |

• Adults: 18%

• Adolescents: 11% |

Note that Adolescents consume the most fructose, but the least amount of whole fruits. They're getting most of their fructose from added sugars, particularly, soft drinks. This is a very worrisome trend.

The problem, I feel, is that so many foods and beverages contain HFCS and added sugar. 77% of all calories purchased in the US between 2005 and 2009 contained a caloric sweetener (Ng SW, et al. 2012). Even if you don't drink soda pop, you are still ingesting fructose in small amounts from a variety of foods, perhaps every single day. Look closely at food labels: you will see HFCS in ketchup, tomato sauces, chocolate milk, and even multi-grain breads.

Considering that fructose can (a) suppress the signal in the brain to stop eating, and (b) induce fat synthesis, I believe people struggling to lose weight should carefully evaluate the foods and beverages they consume on a regular basis and look not only for the total calorie count, but, also, if it contains HFCS and/or "Added Sugars" (see "FOOD LABELS" below).

Fructose and Metabolic Syndrome

Fructose increases triglyceride levels (Havel PJ. 2005). And there is evidence that this process is worse in people with insulin resistance (Abraha A, et al. 1998). Insulin resistance means that the actions of insulin are less effective, and this occurs in people who are obese or who have a condition known as "metabolic syndrome."

Currently, 23% of the adult population has metabolic syndrome (NHANES data 2009-2010, Benjamin EJ, et al. 2017). These people should be especially diligent about reducing their consumption of foods sweetened with HFCS and/or sugar.

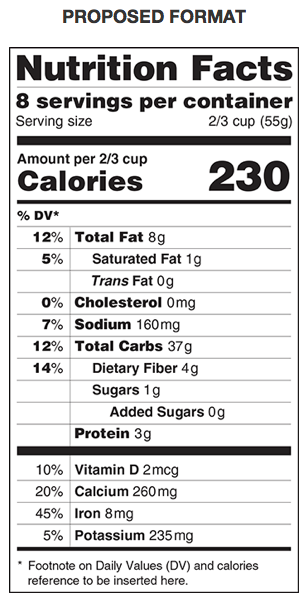

FOOD LABELS

The "Nutrition Facts" panel on packaged foods in the US provides some useful information. The FDA mandated new changes to the standard format (seen in the image to the right). The deadline for compliance is January 2020 for food manufacturers with sales of $10 million or more. The deadline for smaller manufacturers is January 2021.

As before, "Total Carbohydrates" are listed. This is the amount of all carbs: starches, sugars, and fiber. In the new format, a specific line for "Added Sugars" now appears. This represents sugars that have been added during processing.

At the bottom of the panel (not shown here), there is a section called "Ingredients." Here is where HFCS and other sweeteners would be listed. However specific amounts are not provided in this section of the label.

Thus, it's still not possible to calculate the actual amount of fructose or HFCS in a specific food or beverage from the information that currently appears on food labels.

Pay particular attention to foods and beverages that claim to be "Fat Free" or state "No High Fructose Corn Syrup":

• "Fat Free" items: In the process of removing fat, food manufacturers have added various types of sugars to maintain an appealing taste. "Fat Free" half-and-half, "Fat Free" ranch dressing...many of these food products contain HFCS or other added sweetener.

• "No High Fructose Corn Syrup": The label for some processed foods and beverages states "No High Fructose Corn Syrup." However, even healthy-sounding foods and beverages might be loaded in added (unwanted!) sugar.

Here are just 3 examples of foods that state "No High Fructose Corn Syrup" on the package, yet they contain lots of added sugars:

• For Fig Newtons, "corn syrup" is actually listed in the Ingredients list!

• For Post's "Great Grains Cereal," their Nutrition Facts panel lists "Other Carbohydrates." After "Dietary Fiber" and "Sugars" (ie., the naturally-occurring sugars in the fruit), what else could it be? Almost certainly, this line pertains to the amount of added sugars. However, instead of using that name, it appears they have chosen to use the nebulous phrase "Other Carbohydrate". (We assume that they will modify their Nutrition Facts panel when the new regulations go into effect in January 2020...) If, indeed "Other Carbohydrate" does represent "Added Sugar," then 31 grams is roughly 8 teaspoons! That's like pouring most of a can of soda pop on your cereal.

| ITEM |

LABEL SAYS "NO HFCS",

BUT IT CONTAINS: |

Nabisco

Fig Newtons |

In 2 cookies:

"Sugars 24 g":

• sugar

• corn syrup

• invert sugar |

Post

Great Grains Cereal -

raisins, dates, pecans |

In 1 cup:

"Sugars 17 g"

"Other Carbs 31 g":

• brown sugar

• sugar |

Quaker

Real Medleys Oatmeal -

apple walnut |

In 1 cup:

"Sugars 23 g":

• brown sugar

• sugar |

Playing games with names just confuses consumers. And a descriptive term like "Other Carbohydrate" isn't helpful at all.

Food and beverage labels should report the specific number of grams of fructose when an item contains that sugar. Certainly, that's much more important to know, than, say, the amount of Vitamin A, which isn't a required detail either, yet it appears on the Nutrition Facts panel of many foods. Unfortunately, reporting the amount of fructose on food labels isn't required, so it's likely we won't see that detail for many more years.

DON'T WORRY ABOUT THE NATURAL FRUCTOSE IN FRUIT

Up to this point, I've only discussed the health risks of fructose when consumed as sugar and/or HFCS. What about the fructose in fruit?

It turns out that the fructose that occurs naturally in fruits doesn't pose the same health risks as the fructose in sugar or HFCS:

• Study #1: Way back in 1971, a small study had people consume 20 servings of fruit per day for 12-24 weeks. It was estimated that these subjects consumed about 200 grams of fructose per day. Yet, despite this high intake, no worsening of body weight, blood glucose, insulin levels, or lipid levels were seen! (Meyer BG, et al. 1971) (Ludwig DS. 2013).

• Study #2: In 2009, 131 subjects were put on 1 of 2 diets for 6 weeks: a very low natural fructose diet or a moderate natural fructose diet. More specifically:

- All subjects (both groups) consumed 55% of their daily calories as carbohydrates.

- No one (in either group) consumed any "added sugars": candies, snacks, soft drinks, fruit juices.

- The low fructose diet group consumed 3-4% of their calories as natural fruit; the moderate fructose diet group consumed 30%.

The moderate fructose diet group consumed about 500 calories per day as fruit. (This is less than half of what the people in the 1971 study consumed.) But what's interesting is that after 6 weeks, many health parameters in the moderate fructose diet group were actually better than those on the low fructose diet: blood levels of cholesterol, glucose, and triglycerides declined slightly more in the group that consumed more fruit (Madero M, et al. 2011).

This suggests that other nutrients in fruit (antioxidants, vitamin C, fiber, polyphenols, potassium, etc.) may somehow override any detrimental effects that fructose might cause.

So, don't worry about the fructose that occurs naturally in fruit. However, canned fruit in heavy syrup may contain lots of added sugars. Minimize your consumption of canned fruit. Eat fruit in its natural state.

WHAT ABOUT THE FRUCTOSE IN SPORTS DRINKS LIKE GATORADE® and POWERADE®?

What does this topic have to do with exercising, fitness, and athletic performance?

It's relevant because most sports drinks contain fructose.

Keep in mind that there's much less fructose in sports drinks than in soda-pop, energy drinks, or apple juice:

Original Gatorade® ("Thirst Quencher") has a carbohydrate concentration of 5.8%. That means there are 21 grams of carbs in a 12-oz. serving. Compare that to Coca-Cola®:

| BEVERAGE |

AMT. OF CARBS

(per 12-oz.) |

| Gatorade® (original) |

21 g per 12-oz. |

| Coca-Cola® |

39 g per 12-oz. |

Note that these amounts are "Total Carbohydrates". We can't calculate the specific amount of fructose because we can't be certain what percent of the total comes from fructose.

Also, note that the use of simple sugars (such as glucose and fructose) in combination has been found to be the optimum formula for fueling your body during exercise. "Simple" carbohydrates are absorbed more readily from the GI tract than complex carbs, and, using several simple carbs together (in a sports drink) also allows for more efficient absorption as compared to a solution containing only a single carbohydrate.

Bottom line: Not exercising regularly is a lot worse for your health than consuming the relatively small amounts of fructose from sports drinks:

• When laboratory rats were fed a high-fructose diet and not allowed to run, in as little as 2 weeks their blood pressure increased and metabolic changes were seen. However, in rats that were allowed to run, the effects of the high-fructose diet were minimized (Reaven GM, et al. 1988).

Until they come up with something better, don't worry about sports drinks that contain "glucose-fructose syrup"....just get out there and exercise 5-7 days per week! Nevertheless, even if you do exercise regularly, it's still smart to minimize your consumption of sugar and HFCS.

SUMMARY

Fructose, when consumed from unnatural sources as sugar and HFCS, causes very unique and puzzling metabolic effects. These actions, in turn, contribute to obesity, lipid disorders, and metabolic syndrome.

In general, avoid products containing high-fructose corn syrup as much as you can. But, good luck with that! HFCS is now in thousands of processed foods. And even if a food or beverage states "No High Fructose Corn Syrup," it could still contain lots of added sugars in other forms.

So, be judicious about reading the labels on foods and beverages. Specifically, look for the following:

• Main Nutrition Facts Panel: Here, look at the Carbohydrates section. Beginning January 2020, "Added Sugars" will be required on foods and beverages from large manufacturers. This detail will also be required for smaller manufacturers beginning January 2021. Always select foods and beverages with as little "Added Sugars" as possible.

• Ingredients List: Due to the negative publicity of high-fructose corn syrup, food manufacturers may not list it by that name on food labels. There are many other names for sugar, too: cane syrup, agave syrup, etc., etc. You'll have to be diligent to avoid, or minimize, these products.

• Be Wary of "Fat-Free" Foods: Many fat-free foods replace the fat with sugar.

• Stop Drinking Soda Pop: Trust me when I tell you that the caffeine in soda pop is the least of your concerns.

• Don't Worry About the Fructose in Fruits: Don't worry about the fructose that occurs naturally in fruit. However, minimize your consumption of canned fruit in "heavy syrup."

• Sports Drinks: The small amount of fructose in sports drinks isn't a concern. For people who are exercising hard, or, longer than 60 minutes, consuming simple sugars like glucose and fructose are precisely what your muscles need!

FOR MORE INFORMATION

The best web site for information on glycemic index and glycemic load is www.GlycemicIndex.com,

maintained by the University of Sydney. Unfortunately, the glycemic index value for most manufactured food products has not yet been determined.

Although it is intended to be an academic text, "Perspectives In Nutrition" (by Wardlaw, Hampl, and DiSilvestro) is a nutrition book that most consumers could use. The information is written in easy to understand language, and, the multitude of colorful diagrams, tables, and pictures

help to explain the concepts. The Appendix alone is 203 pages! Read our review.

Readers may also be interested in the following related articles:

EXPERT HEALTH and FITNESS COACHING

Stan Reents, PharmD, is available to speak on this and many other exercise-related topics. (Here is a downloadable recording of one of his Health Talks.) He also provides a one-on-one Health Coaching Service. Contact him through the Contact Us page.

REFERENCES

Abraha A, Humphreys SM, Clark ML, et al. Acute effect of fructose on post-prandial lipaemia in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects. Br J Nutr 1998;80:169-175. Abstract

Benjamin EJ, Blaha MJ, Chiuve SE, et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics: 2017 update. Circulation 2017;135:e146-e603. Abstract

Bravo S, Lowndes J, Sinnett S, et al. Consumption of sucrose and high-fructose corn syrup does not increase liver fat or ectopic fat deposition in muscles. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 2013;38:681-688. Abstract

Bray G, Nielsen S, Popkin B. [Letter to the editor]. Am J Clin Nutr 2004a;80:1447-1448. (no abstract)

Bray GA, Nielsen JN, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 2004b;79:537-544. Abstract

DiNicolantonio JJ, O'Keefe JH, Lucan SC. Added fructose: A principal driver of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its consequences. Mayo Clinic Proc 2015;90:372-381. Abstract

Gersch MS, Mu W, Cirillo P, et al. Fructose, but not dextrose, accelerates the progression of chronic kidney disease. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007;293:F1256-F1261. Abstract

Havel PJ. Dietary fructose: Implications for dysregulation of energy homeostasis and lipid/carbohydrate metabolism. Nutr Rev 2005;63:133-157. Abstract

Krilanovich NJ. Fructose misuse, the obesity epidemic, the special problems of the child, and a call to action. Am J Clin Nutr 2004;80:1446-1447. Abstract

Le K-A, Faeh D, Stettler R, et al. A 4-week high-fructose diet alters lipid metabolism without affecting insulin sensitivity or ectopic lipids in healthy humans. Am J Clin Nutr 2006;84:1374-1379. Abstract

Ludwig DS. Examining the health effects of fructose. JAMA 2013;310:33-34. (no abstract)

Ma J, Fox CS, Jacques PF, et al. Sugar-sweetened beverage, diet soda, and fatty liver disease in the Framingham Heart Study cohorts. J Hepatology 2015;63:462-469. Abstract

Madero M, Arriaga JC, Jalal D, et al. The effect of two energy-restricted diets, a low-fructose diet versus a moderate natural fructose diet, on weight loss and metabolic syndrome parameters: A randomized controlled trial. Metabolism 2011;60:1551-1559. Abstract

Maersk M, Belza A, Stodkilde-Jorgensen H, et al. Sucrose-sweetened beverages increase fat storage in the liver, muscle, and visceral fat depot: A 6-month randomized intervention study. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:283-289. Abstract

Meyer BG, de Bruin EJ, Du Plessis DG, et al. Some biochemical effects of a mainly fruit diet in man. S Afr Med J 1971;45:253-261. (no abstract)

Nakagawa T, Tuttle KR, Short RA, et al. Hypothesis: fructose-induced hyperuricemia as a causal mechanism for the epidemic of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Clin Pract Nephrol 2005;1:80-86. Abstract

Nakagawa T, Hu H, Zharikov S, et al. A causal role for uric acid in fructose-induced metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2006;290:F625-F631. Abstract

Ng SW, Slining MM, Popkin BM. Use of caloric and noncaloric sweeteners in US consumer packaged foods, 2005-2009. J Acad Nutr Dietetics 2012;112:1828-1834. Abstract

Park YK, Yetley EA. Intakes and food sources of fructose in the United States. Am J Clin Nutr 1993;58 (5 Suppl):737S-747S. Abstract

Parks EJ. Effect of dietary carbohydrate on triglyceride metabolism in humans. J Nutr 2001;131:2772S-2774S. Abstract

Parks EJ, Skokan LE, Timlin MT, et al. Dietary sugars stimulate fatty acid synthesis in adults. J Nutr 2008;138:1039-1046. Abstract

Reaven GM, Ho H, Hoffman BB. Attenuation of fructose-induced hypertension in rats by exercise training. Hypertension 1988;12:129-132. Abstract

Schwimmer JB, Ugalde-Nicalo P, Welsh JA, et al. Effect of a low free sugar diet vs usual diet on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adolescent boys. A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2019;321:256-265. Abstract

Stanhope KL, Griffen SC, Bair BR, et al. Twenty-four-hour endocrine and metabolic profiles following consumption of high-fructose corn syrup-, sucrose-, fructose-, and glucose-sweetened beverages with meals. Am J Clin Nutr 2008;87:1194-1203. Abstract

Swarbrick MM, Stanhope KL, Elliott SS, et al. Consumption of fructose-sweetened beverages for 10 weeks increases postprandial triacylglycerol and apolipoprotein-B concentrations in overweight and obese women. Br J Nutr 2008;100:947-952. Abstract

Tan D, Wang Y, Lo CY, et al. Methylglyoxal: its presence and potential scavengers. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr 2008;17 suppl.1:261-264. Abstract

Taylor EN, Curhan GC. Fructose consumption and the risk of kidney stones. Kidney Int 2008;73:207-212. Abstract

Ventura EE, Davis JN, Goran MI. Sugar content of popular sweetened beverages based on objective laboratory analysis: Focus on fructose content. Obesity 2011;19:868-874. Abstract

Vos MB, Kimmons JE, Gillespie C, et al. Dietary fructose consumption among US children and adults: The Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Medscape J Med 2008;10(7):160. Abstract

Walker RW, Dumke KA, Goran MI. Fructose content in popular beverages made with and without high-fructose corn syrup. Nutrition 2014;30:928-935. Abstract

White JS, Hobbs LJ, Fernandez S. Fructose content and composition of commercial HFCS-sweetened carbonated beverages. Int J Obesity 2015;39:176-182. Abstract

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stan Reents, PharmD, is a former healthcare professional. He is a member of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). In the past, he has been certified as a Health Fitness Specialist by ACSM, as a Certified Health Coach by ACE, as a Personal Trainer by ACE, and as a tennis coach by USTA. He is the author of Sport and Exercise Pharmacology (published by Human Kinetics) and has written for Runner's World magazine, Senior Softball USA, Training and Conditioning and other fitness publications.

Browse By Topic:

diabetes, energy drinks, food labels, health and fitness targets, obesity, sports drinks, sports nutrition

Copyright ©2026 AthleteInMe,

LLC. All rights reserved.

|