|

Not Enough Exercise vs. Too Much Sitting

Author:

Stan Reents, PharmD

Original Posting:

04/29/2018 08:53 AM

Last Revision: 05/15/2019 08:52 AM

People who are sedentary have an increased risk of back pain, cancer, coronary disease, dementia, depression, diabetes, hypertension, metabolic syndrome, and osteoporosis compared to those who exercise regularly. I've written extensive reviews of how exercise can be helpful for all of these conditions. They are available in our Articles Library.

But stating that being sedentary all week long for months and months can lead to health problems is no longer newsworthy...everyone knows this.

However, what a lot of people may not realize is that prolonged sitting causes metabolic changes that pose health risks even if you meet the current daily exercise goals. In other words, "not enough exercise" and "too much sitting" can each -- independently -- cause health problems.

HOW CAN YOU BE ACTIVE AND SEDENTARY AT THE SAME TIME?

First off, let's clarify -- there's a difference between "exercise" and "physical activity": "Exercise" is what you do when you go to the gym: running on a treadmill, working out on an elliptical machine, etc. "Physical activity" is represented by routine house chores. It could be mild effort (vacuuming), or very intense (digging a shrub out of the ground). Being "sedentary" means just sitting...

While lots of people are sedentary all day long -- 28% of Americans, according to annual surveys conducted by the Physical Activity Council (see below) -- virtually no one can exercise or be active continuously from the time they get up until the time they go back to bed.

So, while of course you can't be active and sedentary simultaneously, all of us spend time in both categories during any given day.

For most people, an exercise session rarely lasts more than 60 minutes. And even those who exercise more than that will spend some portion of the day sitting.

This led researchers to investigate what a mixture of exercise and sitting does to our health...

The Australian "45 and Up" Study

Researchers from the University of Western Sydney, in Sydney, Australia, analyzed data from 63,000 men, ages 45-64 years old, as part of the "45 and Up" Study (George ES, et al. 2013). The 45 and Up Study has collected data on 267,000 individuals in New South Wales.

Subjects were grouped according to how much time they spent sitting per day:

- 0-4 hours per day

- 4-6 hours per day

- 6-8 hours per day

- more than 8 hours per day

Then, they analyzed the activity levels of these men, and what chronic diseases they had.

They found that as the hours of sitting increased, so did the risk of diabetes and high blood pressure. (The association between hours of sitting and the risk of heart disease was not quite as strong.) More importantly, this association held true even when they accounted for how much exercise these men did.

The "Canada Fitness Survey" Study

Peter Katzmarzyk, PhD, and colleagues, analyzed data from 17,000 adults, ages 18-90 years old, who participated in the Canada Fitness Survey (CFS) (Katzmarzyk PT, et al. 2009).

In this analysis, subjects were grouped into 1 of 5 categories based on how much time they spent sitting:

- almost none of the time

- one-fourth of the time

- half of the time

- three-fourths of the time

- almost all of the time

Researchers followed these people for an average of 12.9 years. They found that the rate of death from cancer, cardiovascular disease, and other causes increased as the amount of time spent sitting increased.

But, as with the Australian study described above, what mattered was how much sitting occurred: the relationship between too much sitting and an increased rate of death was similar in the group of people who met the standard exercise recommendation (ie., 30 minutes of brisk walking per day) compared to those who didn't!

THE PHYSIOLOGY OF BEING SEDENTARY

Here's the perplexing part of this discussion: How can you still be at risk for health problems if you are meeting current exercise recommendations (eg., walking briskly for 30 minutes per day)? After all, the "official" exercise recommendations are based on decades of research.

Answer: Because it only takes several hours for our metabolism to start changing in response to becoming sedentary.

One of the leading researchers investigating what happens to our metabolism when we sit all day is Marc Hamilton, PhD, a professor in the Department of Health and Human Performance at the University of Houston.

Beginning in 2003, Dr. Hamilton and others have shown how rapidly metabolism can change:

• In one study, the enzyme "lipoprotein lipase" (LPL) in the leg muscles of rats showed a dramatic decline in activity within only 6 hours of immobilizing these muscles. After 18 hours of no muscular contractions, LPL activity declined by 90-95%! Then, when normal treadmill walking was resumed, LPL activity increased 8-fold within 4 hours (Bey L, et al. 2003). This enzyme is involved in making triglycerides (an important energy source!) available to muscle cells. Thus, this research helps explain why people who are sedentary often have elevated triglyceride blood levels...ie., it's not being taken up by muscle cells.

If it only takes several hours for our metabolism to slow down in response to sitting, this begins to explain how being sedentary can offset the health gains obtained by your exercise session!

There's more bad news regarding sitting (being sedentary). Your aerobic fitness level (VO2max) also worsens rapidly when you stop exercising:

• A 49-yr old female cyclist was sidelined when she broke her collarbone. Her VO2max declined from 56 ml/kg/min to 42 ml/kg/min (a 26% decrease) over a period of 32 days of rest. Eleven weeks of training brought it back up to pre-injury levels (Nichols JF, et al. 2000).

An incredible study performed in the 1960's puts this into perspective:

• Five healthy men in their 20's remained on bed rest for 3 weeks. Their VO2max decreased during this period from 43 to 31 ml/kg/min. That's a 28% drop! Then, after 2 months of training (walking, jogging), a repeat VO2max of 51 ml/kg/min was determined. Thirty years later, when these same men were 50 years old, their VO2max value was again down to 31 ml/kg/min (Saltin B. 2002).

The conclusion here is that 3 weeks of sedentary behavior causes the same reduction in aerobic fitness as does 30 years of aging!

In my opinion, your aerobic fitness is the most critical physiologic variable affecting your health. So, if aerobic fitness can decrease that fast, this, too, explains why too much sitting is bad for our health.

THE REALLY BAD NEWS

But wait, this story gets even worse:

The massive NIH-AARP Diet and Health Study followed 240,000 adults, ages 50-71 yrs, for 8 years. Like the other studies already summarized, this study also documented an increased risk of death (all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and cancer mortality) as the amount of sitting time increased (Matthews CE, et al. 2012).

However, instead of evaluating whether these people met the standard exercise guidelines or not, they evaluated how much time they spent in "moderate or vigorous physical activity", which is more inclusive. This would include not only a 30-minute exercise session, but, also, the 2 hours spent mowing the lawn, for example. Researchers found that those who watched TV for 7 or more hours per day still had twice the risk of death from cardiovascular disease even if they participated in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity for 7 or more hours that day!!

The take-away message from this is that it is more critical to reduce the time you spend sitting than to increase your daily activity! Too much sitting offsets the health benefits of exercise and daily physical activity!

HOW MUCH TIME DO WE SPEND SITTING?

The implications of these metabolic and physiologic changes associated with being sedentary are brought into focus when we look at how much sitting we do:

• Australia: In the Australian study described above, 33% of the men reported sitting for 8 hours or more each day (George ES, et al. 2013).

• Canada: In the Canadian study described above, 17% reported sitting for three-fourths of the day or longer (Katzmarzyk PT, et al. 2009).

• UK: A 2007 poll conducted in the UK revealed that adults there spend 63 hours per week sitting.

• USA: Various surveys show how sedentary Americans are: Analysis of data from the 2003-2004 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) revealed that Americans spent 7.7 hours per day sitting (Matthews CE, et al. 2008). The Physical Activity Council reported that every year from 2012 to 2017, 28% of Americans were inactive. What's even more concerning about these stats is that adolescents and kids as young as 6 years old were included.

• USA: How much physical activity Americans obtain at work is decreasing. Data were obtained from the Current Employment Statistics (CES) Program for the years 1960 to 2008. The percentage of sedentary jobs has risen steadily during this time period. It was determined that men are burning 140 calories per day less and women are burning 124 calories per day less during work hours compared to 1960 (Church TS, et al. 2011).

THE GOOD NEWS

So far, I've only discussed how being sedentary can offset the health benefits of exercise. What if you do stay active throughout the day?

Here, there is some good news:

Just as research during the past decade has revealed that sitting all day poses health risks, it has also been determined that staying active every day -- ie., doing house chores like mowing the lawn, gardening, etc. -- can actually help to prevent these same health concerns.

The health benefits of "daily physical activity" (ie., not traditional exercise) became profoundly evident when Dan Buettner and colleagues investigated why some populations of people live to 100, largely disease-free. Buettner first revealed the behaviors of these populations in an article published in National Geographic magazine in 2005. He followed that up with books titled "The Blue Zones". (see our review of the 2nd edition here.)

Five populations of people around the world were studied. From these investigations, 9 common behaviors were realized. One of them was that these people simply do NOT sit around all day long. Most of them are doing chores every day: working in the garden, tending to their goats, pigs, and sheep, walking to the market, etc.

Further, most of these Blue Zones people don't belong to a gym. And they don't have a treadmill in their house either. They don't "exercise" in the classic sense.

Researchers now recognize that daily "physical activity" provides substantial health benefits...even if you don't exercise!

SO, IS IT REALLY NECESSARY TO EXERCISE?

OK, the Blue Zones people don't exercise yet live to 100 and avoid chronic disease by staying active all day long. However, people who do exercise are still at risk for health problems if they sit too much.

This brings up the question: Are current national exercise guidelines -- eg., to walk briskly for 30 minutes per day -- misleading? Maybe we should focus on being more active throughout the day and be less concerned about obtaining a 30-minute bout of exercise?

A key principle in answering this question requires making a distinction between "maintaining our health" vs. "improving our fitness." Mowing your lawn with a push mower, gardening, washing the car, painting the house...these physical activities are now recognized to be beneficial for maintaining your health: keeping your blood pressure, your weight, and various metabolic parameters (eg., glucose, triglycerides) under control.

However, if you want to run a 5-K race, or play in a tennis tournament, you will likely need to do some "traditional" aerobic exercise: jogging, bicycling, working out on an elliptical machine, swimming, etc. The key here is to get your heart rate up and keep it up for a sustained period of time.

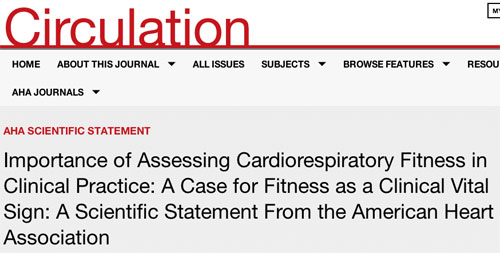

Your aerobic fitness (VO2max) is critical for sports performance. But the medical profession is now recognizing how important your aerobic fitness is for your health, too. In November 2016, the American Heart Association formally recommended that physicians routinely monitor the aerobic fitness level of patients (Ross R, et al. 2016):

This shifts the focus back on exercise. So, which is more important? staying active throughout the day, or, doing traditional exercise?

The answer is that both are important, but for different reasons.......

Some people (like me!) don't want to join a gym and don't like the boring repetition of running on a treadmill or riding a stationary bike. Other people may be so busy during the day that they simply can't find time to exercise. This description applies to some physicians!

Here, there's more good news: It turns out that you don't have to exercise like an Olympic athlete to improve your fitness. Yes, really...

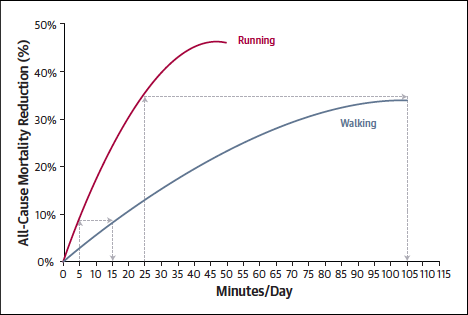

In August 2014, researchers reported in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology that running was a lot more effective than walking than previously thought (Wen, et al. 2014). Current exercise guidelines recommend 30 minutes of walking or 20 minutes of running. But, this new research suggests that as little as 8 minutes of running equates to 30 minutes of walking:

Further, for many decades, it's been known that doing short, high-intensity bursts of running ("Fartlek") can improve your VO2max. But, more recently, doing short bursts is also beneficial for specific health problems. I've covered this in detail my review "Interval Training."

"STEPS" YOU SHOULD TAKE

Stop and think how much sitting you do during a typical week: in your car, at work, texting, surfing the Internet, and, of course, watching TV. Here are some tips on adding more physical activity into your weekly routine:

Don't Do This:

• Don't use the drive-through at the bank, the cleaners, and fast-food restaurants.

• Don't use the valet to park your car.

• Don't use a golf cart when you play golf.

Instead, Do This:

• Park as far away from the front door as you can when you go to the grocery store, the bank, the cleaners, the post office, the mall, and when you make other stops.

• When you can, take the stairs instead of the elevator or escalator.

• Wash your car by hand instead of using an automated car wash.

• Use a push mower instead of a riding mower.

• If you have a desk job, stand up and walk around the office every hour or 2.

• Buy an activity tracker that alerts you when you've been sitting for longer than an hour. One model that does that is Garmin's VivoFit-2. We've profiled a bunch of them here: Activity Trackers

• Reduce how much time you spend interacting with your smart-phone, your tablet, and your computer.

Sitting all day long is the new smoking. Don't do it!

FOR MORE INFORMATION

Readers may be interested in these reviews:

EXPERT HEALTH and FITNESS COACHING

Stan Reents, PharmD, is available to speak on this and many other exercise-related topics. (Here is a downloadable recording of one of his Health Talks.) He also provides a one-on-one Health Coaching Service. Contact him through the Contact Us page.

REFERENCES

Bassett DR, Freedson P, Kozey S. Medical hazards of prolonged sitting. Exercise Sports Science Reviews 2010;38:101-102. (no abstract)

Bey L, Hamilton MT. Suppression of skeletal muscle lipoprotein lipase activity during physical inactivity: A molecular reason to maintain daily low-intensity activity. J Physiology 2003;551:673-682. Abstract

Church TS, Thomas DM, Tudor-Locke C, et al. Trends over 5 decades in US occupation-related physical activity and their associations with obesity. PLoS ONE 2011;6(5):e19657. Abstract

George ES, Rosenkranz RR, Kolt GS. Chronic disease and sitting time in middle-aged Australian males: Findings from the 45 and Up Study. Int J Behav Nutr Physical Activity 2013;10:20. Abstract

Grontved A, Hu FB. Television viewing and risk of type-2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and all-cause mortality. A meta-analysis. JAMA 2011;305:2448-2455. Abstract

Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Exercise physiology versus inactivity physiology: An essential concept for understanding lipoprotein lipase regulation. Exercise Sports Science Reviews 2004;32:161-166. Abstract

Hamilton MT, Hamilton DG, Zderic TW. Role of low energy expenditure and sitting in obesity, metabolic syndrome, type-2 diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Diabetes 2007;56:2655-2667. Abstract

Hamilton MT, Healy GN, Dunstan DW, et al. Too little exercise and too much sitting: Inactivity physiology and the need for new recommendations on sedentary behavior. Curr Cardiovasc Risk Rep 2008;2:292-298. Abstract

Henson J, Yates T, Biddle SJH, et al. Associations of objectively measured sedentary behaviour and physical activity with markers of cardiometabolic health. Diabetologia 2013;56:1012-1020. Abstract

Katzmarzyk PT, Church TS, Craig CL, et al. Sitting time and mortality from all causes, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2009;41:998-1005. Abstract

Matthews CE, Chen KY, Freedson PS, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors in the United States, 2003-2004. Am J Epidemiology 2008;167:875-881. Abstract

Matthews CE, George SM, Moore SC, et al. Amount of time spent in sedentary behaviors and cause-specific mortality in US adults. Am J Clin Nutr 2012;95:437-445. Abstract

Nichols JF, Robinson D, Douglass D, et al. Retraining of a competitive master athlete following traumatic injury: a case study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2000;32:1037-1042. Abstract

Owen N, Healy GN, Matthews CE, et al. Too much sitting: The population health science of sedentary behavior. Exercise Sports Science Reviews 2010;38:105-113. Abstract

Physical Activity Council 2018 Participation Report: http://PhysicalActivityCouncil.com/PDFs/current.pdf (accessed April 26, 2018).

Ross R, Blair SN, Arena R, et al. Importance of assessing cardiorespiratory fitness in clinical practice: a case for fitness as a vital sign. Circulation 2016;134:e653-e699. Abstract

Saltin B. Myths about aerobic fitness. AJMS 2002;109-110. (no abstract)

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Stan Reents, PharmD, is a former healthcare professional. He is a member of the American College of Lifestyle Medicine (ACLM) and a member of the American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM). In the past, he has been certified as a Health Fitness Specialist by ACSM, as a Certified Health Coach by ACE, as a Personal Trainer by ACE, and as a tennis coach by USTA. He is the author of Sport and Exercise Pharmacology (published by Human Kinetics) and has written for Runner's World magazine, Senior Softball USA, Training and Conditioning and other fitness publications.

Browse By Topic:

exercise and health, exercise guidelines, exercise information, exercise recommendations

Copyright ©2026 AthleteInMe,

LLC. All rights reserved.

|