|

Exercise For Coronary Artery Disease

Author:

Stan Reents, PharmD

Original Posting:

08/27/2013 11:13 AM

Last Revision: 01/19/2021 12:29 PM

Can you name the #1 cause of death in adults in the US? If you answered "breast cancer" or "obesity" you would be wrong. While these diseases are frequent topics for the news media, they are not even in the top 3. Can you name the #1 cause of death in adults in the US? If you answered "breast cancer" or "obesity" you would be wrong. While these diseases are frequent topics for the news media, they are not even in the top 3.

The #1 cause of death in adults is: cardiovascular disease. In fact, except for 1918, when there was an influenza outbreak in the US, cardiovascular disease has been the #1 cause of death (in adults) every single year since 1900! CARDIOVASCULAR DISEASE "Cardiovascular disease" represents a collection of distinct disease states: coronary artery disease (CAD), hypertension, stroke, congestive heart failure, and several others. (NOTE: In medical publications, the term "coronary heart disease" is used. I'm going to use the term "coronary artery disease" because it emphasizes that the problem lies in the coronary arteries.) Together, these cardiovascular diseases affect more than 92 million Americans. It's estimated that more than 1 in 3 adults has one or more risk factors for cardiovascular disease (Benjamin EJ, et al. 2018). Many people think that this is a man's disease. However, currently, more women than men die of cardiovascular disease annually in the US. Cardiovascular disease kills 10 times as many women each year than does breast cancer (see table below). In fact, cardiovascular disease kills more women than the next 14 causes of death combined. The table below summarizes some mortality statistics from the American Heart Association Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics - 2018 Update (Benjamin EJ, et al. 2018). The stats on breast cancer are provided to illustrate how many more women die from CVD and from CAD each year:

| CAUSE OF DEATH | NO. OF DEATHS,

Men (2009) | NO. OF DEATHS,

Women (2009) | • Cardiovascular

disease (all forms) | 386,436 | 401,495 | • Coronary

artery disease | 210,069 | 176,255 | | • Breast cancer | n/a | 40,678 |

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE Coronary artery disease (CAD) is the most common cause of deaths due to cardiovascular disease: 44%. This is a far greater percentage than deaths due to either hypertension or stroke (Benjamin EJ, et al. 2018):

| CAUSE OF DEATH | PERCENT OF ALL

CARDIOVASCULAR DEATHS,

adults (2015) | • Coronary artery

disease | 44% | | • Stroke | 17% | | • Hypertension | 9% |

Roughly 915,000 myocardial infarctions (heart attacks) occurred during 2009 in the US. How would we react if this number represented the number of passengers getting food poisoning on cruise ships, or, the number of toddlers suffering pinched fingers from a particular brand of playpen? My guess is that these corporations would be crucified on social media, and, likely, lawsuits would be filed. However, no similar outcry occurs regarding the major public health problem of heart disease. Why? Certainly, heart attacks are a lot more serious than food poisoning or pinched fingers: Deaths due to a coronary event occur at the rate of approximately one every minute in the US! As such, coronary artery disease deserves more attention than it is currently getting. The media covers breast cancer on nearly a weekly basis, however, we rarely hear about coronary artery disease. Why? More than 4 times as many women die of coronary disease than they do of breast cancer each year. Even worse than the huge number of people dying from coronary disease every year is that the vast majority of these deaths likely could have been prevented. Researchers have estimated that 80-90% of heart disease can be prevented (Kones R. 2011) (Mozaffarian D, et al. 2008). Risk factors for coronary artery disease include: elevated blood pressure, elevated blood lipids, smoking, diabetes, obesity, stress, family history of heart disease, and, most importantly, lack of exercise, specifically, aerobic exercise. Other than "family history," each of these risk factors can be modified with lifestyle changes. It is my opinion that nothing -- absolutely NOTHING -- is more effective for coronary artery disease than aerobic exercise. This review will summarize an extensive amount of medical research on this topic. (For health care professionals, or, those looking for a scholarly discussion of the superiority of lifestyle modification vs. traditional medical treatments for cardiovascular disease, see the superb paper by Dariush Mozaffarian, MD, DrPH, Peter Wilson, MD, and William Kannel MD, MPH in the June 10, 2008 issue of Circulation.) But first: NOTE: Coronary artery disease is a serious health condition. While exercise is clearly one of the best things you can do, talk to your personal physician before you decide to embark on a new exercise program. Then, once you receive the go-ahead, use this article to guide you. A CRITICAL VIEW OF CHOLESTEROL Currently, the treatment of coronary artery disease is based on not smoking, losing weight, lowering cholesterol and blood pressure, and addressing other risk factors, though, substantial emphasis is placed on cholesterol values. Indeed, it has been stated: "Coronary heart disease is uncommon in societies with an average (total) cholesterol of < 180 mg/dL." (Schaefer EJ. 2002). In 1986, an analysis of over 356,000 middle-aged men revealed a strong relationship between the total cholesterol level and the risk of CAD (Stamler J, et al. 1986). But equally impressive arguments against treating patients based only on their cholesterol values have been made. Numerous large research studies offer evidence: • In 1993, Dr. George Davey Smith, an epidemiologist at the University of Glasgow, and his group reviewed 35 research studies in a "meta-analysis" (a scientific analysis of previously-published research on a given topic) to evaluate the effectiveness of lowering cholesterol in reducing the risk of coronary artery disease. They categorized the research according to the patient's baseline level of risk. They found that cholesterol lowering was only effective in reducing the risk of death in patients at "high" risk.....cholesterol-lowering had no benefit in patients with either "moderate" risk or "low" risk. They also analyzed how the cholesterol level was lowered. They found that it didn't matter if cholesterol was lowered with drug therapy or with diet modification.....the same trend appeared, ie., that only patients at high risk benefited (Smith GD, et al. 1993). Cholesterol levels cannot be interpreted in isolation. For example, what are the rates of smoking and high blood pressure in the people included in these studies? And, most importantly, what is their level of daily physical activity and especially their degree of aerobic fitness? In November 2011, a summary of patient data from the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction (NRMI) was published in JAMA (Canto JG, et al. 2011). The investigators analyzed which risk factors were present in 542,000 patients at the time of their first heart attack. Surprisingly, "elevated cholesterol levels" were present in only 1 out of 4 patients:

| RISK FACTOR | PERCENT OF 542,000 PATIENTS

WITH THIS

RISK FACTOR | | • Hypertension | 52% | | • Smoker | 31% | | • Elevated Cholesterol | ** 28% ** | | • Family History of CHD | 28% | | • Diabetes mellitus | 22% |

Unfortunately, this investigation did not assess "aerobic fitness" which, as you will learn, turns out to be the most important factor of all. The case of Mr. Pritikin below also implies that coronary artery disease is directly related to the total cholesterol level. But, in addition to lowering his cholesterol, he also improved his aerobic fitness. A Perspective on LDL-Cholesterol: Assessing "Risk" vs. Preventing Coronary "Events" In my opinion, the "total" cholesterol value (by itself) is not a very useful medical test. In fact, some research shows that total cholesterol levels can be ignored when assessing the risk for cardiovascular disease....assuming other risk factors are considered (Gaziano TA, et al. 2008). This is not so surprising when you realize that the total cholesterol measurement is a summation of several different types of cholesterol, each representing a unique, and, in some ways, an opposing physiologic function: ie., LDL reflects the amount of cholesterol being transported from the liver to storage sites, HDL is a measurement of cholesterol being taken back to the liver. Over time, the medical community has shifted its attention from the total cholesterol value to the LDL fraction. A huge amount of research and medical care is now focused on lowering blood levels of LDL-cholesterol. In the US, the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) has been using LDL-cholesterol levels as the basis of calculating risk and determining treatment strategies for over 2 decades. In their 2004 update (Grundy SM, et al. 2004), virtually every treatment guideline was based on the LDL-cholesterol value. (NOTE: New treatment guidelines were issued in November 2013.) Admittedly, lots of medical research shows that risk goes down as LDL-cholesterol is lowered. Some researchers have calculated that every 1.8 mg/dL reduction in LDL-cholesterol will lead to a 1% reduction in cardiovascular events (Baigent C, et al. 2005). A recent meta-analysis of 27 clinical studies also concluded that risk decreases as LDL levels decrease (Mihaylova B, et al. 2012). However, these are just statistical estimates. What really matters is if heart attacks can be prevented. • Heart Attacks Routinely Occur in Patients with LDL-Cholesterol Levels of 100 mg/dL or Less It turns out that relying on LDL-cholesterol to monitor your vascular health is only partially helpful: When nearly 137,000 patients hospitalized for their first heart attack (ie., no prior history of CAD) were analyzed, it was revealed that 41.5% had an LDL level of less than 100 mg/dL (Sachdeva A, et al. 2009). This is very disturbing because this level of LDL cholesterol is considered desirable for most people, including those with multiple risk factors for CAD. How can we consider an LDL-cholesterol level of 100 mg/dL or lower safe if nearly half of people in that group still have heart attacks? In patients with documented cardiovascular disease, it has been shown that lowering the LDL-cholesterol to a very low 75 mg/dL is even better than a level of 101 mg/dL (Cannon CP, et al. 2006). But, such an aggressive approach isn't necessary for someone who only has an elevated LDL-cholesterol and no other risk factors. And, in patients with multiple risk factors, aggressive lowering of cholesterol does not automatically mean a definite reduction in clinical events (Howard BV, et al. 2008). Yet, even when the LDL-cholesterol is reduced to 70 mg/dL or less, coronary artery disease can still occur: • In the study described above of patients hospitalized for a first heart attack (ie., no prior history of heart disease), 12.5% had an LDL level of less than 70 mg/dL (Sachdeva A, et al. 2009). • In patients with existing coronary artery disease, Cleveland Clinic researchers found that heart disease continued to worsen in 20% of patients even though their average LDL-cholesterol level had been reduced to an extremely low 58 mg/dL. They cautioned to not focus only on the LDL-cholesterol level in patients with established coronary artery disease (Bayturan O, et al. 2010). Why do people with such low LDL-cholesterol levels continue to have coronary disease?!! • Lyon (France) Diet Heart Study The Lyon (France) Diet Heart Study adds even more uncertainty to the reliability of LDL-cholesterol levels. This is the most famous study ever conducted showing that modifying the diet can reduce the risk of coronary disease. In this study, French cardiologist Michel de Lorgeril, MD, and colleagues randomized patients who had already suffered a heart attack into 2 groups: one group received a Mediterranean diet with olive oil while the other group received the standard diet. The benefits of the Mediterranean diet were so dramatic that they stopped the study early. Those results were published in 1994. But, some criticized it saying the study was too short and not enough patients were included. So, de Lorgeril et al. continued it...and this revealed an even more dramatic benefit. The final results were published in 1999. But what's really impressive is that, at the end of the study, both groups had the same LDL-cholesterol level! In fact, it was 161 mg/dL, which is considered elevated by most physicians. How is it you can reduce the risk of heart attacks without reducing LDL-cholesterol levels?!!... CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE IS PREVENTABLE WITHOUT DRUGS! As I mentioned above, it's been estimated that 80-90% of cases of coronary disease are preventable. And even when cholesterol levels are elevated, heart attacks are preventable without using drugs: The Amazing Case of Nathan Pritikin There is no more dramatic example of the power of lifestyle changes to reverse coronary artery disease than the case of Nathan Pritikin: In December 1955, Mr. Pritikin had a total cholesterol level of 280 mg/dL (LDL and HDL fractions were not done back then). At that time, he began to modify his diet. In February 1958, he was diagnosed with asymptomatic coronary insufficiency (ie., inadequate blood flow through the coronaries without producing symptoms of chest pain). At this point, he became much more disciplined about his diet by restricting his consumption of fat and cholesterol. And, he began running. The impact of these changes on his total cholesterol levels are summarized in the table below:

| DATE | AGE | TOTAL

CHOLESTEROL | | Dec. 1955 | 40 | 280 mg/dL | | Feb. 1958 | 42 | 210 mg/dL | | July 1958 | 42 | 162 mg/dL | | Sept. 1958 | 43 | 122 mg/dL | | Aug. 1959 | 43 | 155 mg/dL | | June 1960 | 44 | 120 mg/dL | | Dec. 1963 | 48 | 102 mg/dL | | March 1966 | 50 | 119 mg/dL | | Sept. 1968 | 53 | 118 mg/dL | | Jan. 1969 | 53 | 112 mg/dL | | Nov. 1984 | 69 | 94 mg/dL |

Mr. Pritikin lived for another 27 years after his diagnosis of coronary insufficiency. He died in 1985, at the age of 69. The cause of death was "complications" from lymphoma, not heart disease. Even more remarkable than the fact that he kept his (total) cholesterol at 120 mg/dL or lower for 25 years is what was discovered during his autopsy: when his coronary arteries were opened, there were no raised plaques and there was no constriction of the lumen (the inside diameter of the arteries). Whereas he initially had serious coronary atherosclerosis, he had completely reversed it with only diet and aerobic exercise! This case was published in the New England Journal of Medicine (Hubbard JD, et al. 1985). Mr. Pritikin figured out how to reverse his coronary disease with only lifestyle changes nearly 60 years ago! But keep in mind that he made 2 improvements in his lifestyle: (a) he changed his diet (drastically!) and (b) he substantially improved his aerobic fitness. Unfortunately, we don't know what his actual aerobic fitness level (VO2max) was. Ornish Lifestyle Medicine The Dean Ornish Lifestyle Program (www.Ornish.com) is based on 4 elements: - "moderate"-intensity exercise (most subjects chose walking)

- a vegetarian diet that provides no more than 10% of daily calories from fat

- smoking cessation

- stress-reduction coaching

Consider the results seen in patients who participated in the Dean Ornish "Lifestyle Heart Trial" published in 1998: Coronary angiographies were done on these subjects to evaluate the degree of obstruction in their coronary arteries. After 5 years, even though LDL-cholesterol levels decreased by an identical amount in both groups (the control group received "standard" medical care from their personal physician), coronary lesions improved in the Lifestyle group but worsened in the control group. Most importantly, patients in the Lifestyle program had half the number of coronary "events" than occurred in the control group (Ornish D, et al. 1998):

| AFTER 5 YEARS: | DEAN ORNISH

LIFESTYLE

GROUP | CONTROL

GROUP | | • LDL-cholesterol | decreased 20.1% | decreased 19.3% | • No. of patients taking

lipid-lowering drugs | NONE | >50% | | • Coronary lesions | improved | WORSENED | | • No. of coronary "events" | 25 | 45 |

Why would coronary lesions get worse, and, coronary events be twice as frequent in one group despite an identical reduction in LDL-cholesterol levels? (Answer: The Lifestyle group was exercising more and consuming less total fat in their diet.) These results are even more impressive when you consider that NONE of the Lifestyle group patients were taking lipid-lowering drugs, whereas more than half of the control group were. This research suggests that aerobic exercise and a proper diet are more effective in the management of CAD than lowering cholesterol with drug therapy. Let's recap some of the key points discussed so far: • In one massive study, only 28% of patients suffering a heart attack had an elevated cholesterol (Canto JG, et al. 2011). • Conversely, in another study, 41% of patients had a so-called "acceptable" level of LDL-cholesterol when they had their first heart attack (Sachdeva A, et al. 2009). • The studies of the Ornish Heart Program reveal that changing the diet to reduce cholesterol can lower the risk of a heart attack, but, the Lyon Diet Heart Study showed that risk can be lowered by dietary changes even if LDL-cholesterol levels aren't reduced. Because of all this divergent research, the medical profession has been engaged in an intense debate for years regarding the optimum treatment of elevated cholesterol levels (Peterson ED, et al. 2008): • In a point-counterpoint debate published in the April 11, 2012 issue of JAMA regarding whether a patient with an elevated cholesterol level should receive a statin drug, even the physicians who believed drug therapy was warranted stated: "Clinicians should never treat elevated cholesterol levels in isolation." (Blaha MJ, et al. 2012).  Some clinicians just don't believe that cholesterol is the primary cause of coronary heart disease. In 2012, Jonny Bowden, PhD (he received his PhD in nutrition) and Stephen Sinatra, MD, a board-certified cardiologist, published the book The Great Cholesterol Myth. Regardless of which side of the argument you're on, this book should be read! Some clinicians just don't believe that cholesterol is the primary cause of coronary heart disease. In 2012, Jonny Bowden, PhD (he received his PhD in nutrition) and Stephen Sinatra, MD, a board-certified cardiologist, published the book The Great Cholesterol Myth. Regardless of which side of the argument you're on, this book should be read!

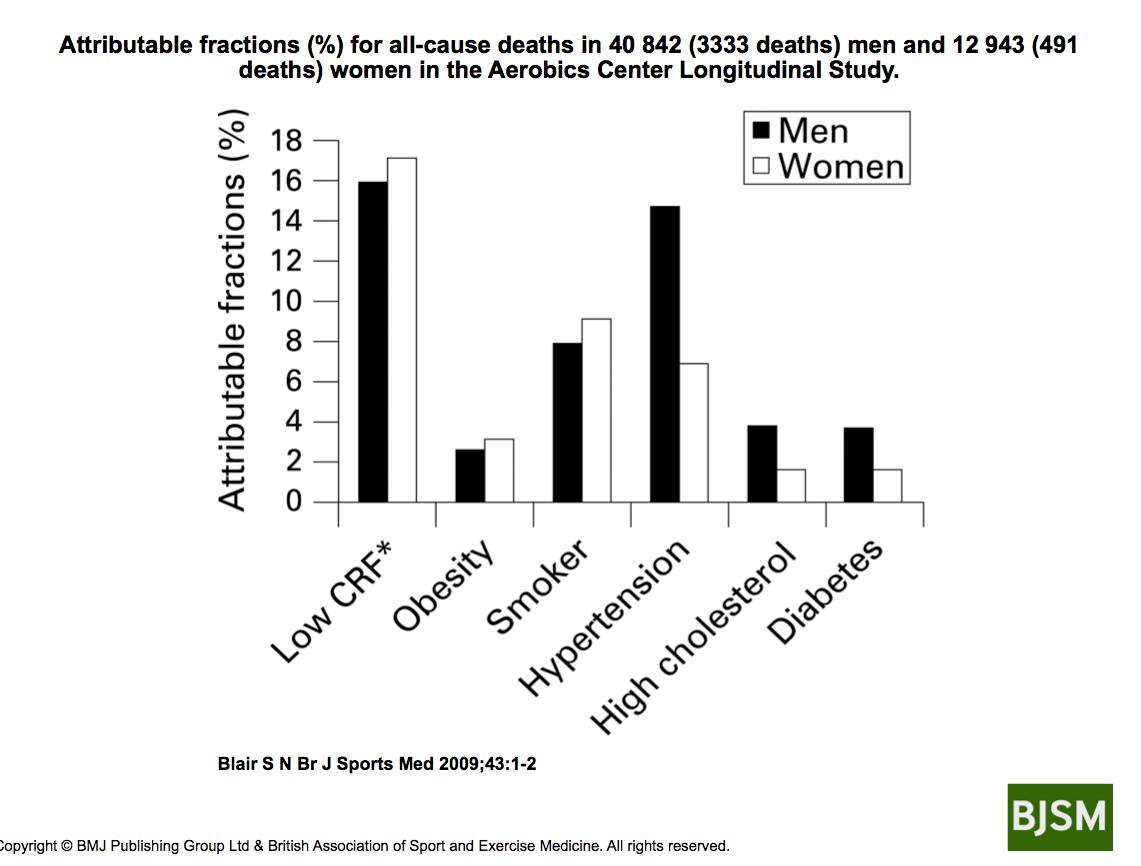

Cholesterol levels don't seem to be a reliable indicator. Is it possible that cholesterol levels don't mean much? LDL-cholesterol levels are not totally meaningless. However, it certainly seems that they can be an unreliable indicator of heart disease risk. An elevated LDL-cholesterol level appears to be less of a concern in the elderly (65 yrs and above) (Fried LP, et al. 1998), and, especially in people whose only risk factor is an elevated cholesterol and who maintain a good degree of aerobic fitness (Blair SN. 2009) (Farrell SW, et al. 2012). Are you confused yet? Don't worry....if leading cardiologists and epidemiologists can't agree on the best way to manage elevated cholesterol levels, how can you decide what to do? What you need to keep in mind is that LDL-cholesterol is only one of several factors that must be considered. And, more importantly, risk factors for heart disease vary in how much they contribute to the risk profile (Blair SN. 2009) (see below). LACK OF AEROBIC EXERCISE (POOR AEROBIC FITNESS), NOT LDL-CHOLESTEROL, IS THE MOST IMPORTANT RISK FACTOR Major research studies published in the 1990's demonstrated a strong relationship between LDL-cholesterol and cardiovascular disease (Downs JR, et al. 1998) (Lancet 1994) (Pitt B, et al. 1995). However, other research provides a different perspective: Numerous other reports have appeared in the medical literature over a span of several decades suggesting the importance of aerobic exercise in preventing heart disease: • In 1961, the autopsy results of a well-known marathon runner Clarence DeMar were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. (Paul Dudley White, MD, the Boston cardiologist who consulted on President Eisenhower when he suffered a heart attack in 1955, was an author of this paper.) Clarence DeMar ran competitively from age 21 until age 69. He was a 7-time winner of the Boston Marathon and a member of 3 Olympic teams. At autopsy, it was revealed that Mr. DeMar's coronary arteries were 2-3 times larger than normal (Currens JH, et al. 1961). Now, admittedly, this doesn't prove that marathon running was the reason for his larger coronary arteries -- the research I summarized below validates that -- but, it sure is darn likely! Mr. DeMar died at age 70.....of cancer, not heart disease. • In 1967, the Framingham Study first reported that physical inactivity was a risk factor for heart disease. • Ralph Paffenbarger, MD, DrPH, with other investigators, published dozens of research studies showing the health benefits of exercise and physical activity. In 1970 and in 1975, he reported that hard physical work in longshoremen reduced death rates from cardiovascular disease (Paffenbarger RS, et al. 1975). • In 1985, cardiologist Paul Dudley White, MD was quoted in the American Journal of Cardiology: "A normal person should exercise 7 hours per week. If you cannot exercise 1 hour per day, make up the difference on the weekend." (Hurst JW. 1985). • In 1992 (finally!), the American Heart Association first recognized that "physical inactivity" was a major risk factor for coronary artery disease. However, 24 years passed before they published their Scientific Statement "Importance of Assessing Cardiorespiratory Fitness in Clinical Practice: A Case for Fitness as a Clinical Vital Sign" in the December 13, 2016 issue of Circulation (Ross R, et al. 2016.) Why has it taken the medical profession so long to embrace exercise as a highly effective therapy for coronary artery disease? Aerobic Exercise Reduces Risk More Than Anything Else You Can Do Ralph Paffenbarger, MD, DrPH, studied the exercise habits and physical activity levels of longshoremen and Harvard alumni and showed how this related to cardiovascular disease. He and co-authors published dozens of studies over a period of several decades demonstrating the health benefits of exercise. In one paper, published in 2000 (Sesso HD, et al. 2000), Paffenbarger and others evaluated the relationship between the amount of weekly "physical activity" (eg., walking, climbing stairs, exercise, sports activities, etc.) and the occurrence of coronary heart disease. Baseline data on these Harvard alumni (men only) were collected in 1977 and they were monitored until 1993. Not surprisingly, as the amount of average weekly physical activity increased, the risk of developing coronary artery disease decreased. However, there were 2 important caveats to this trend: • the reduction in risk of developing coronary heart disease plateaued: above 1999 calories burned per week (equivalent to walking about 3 miles/week), no further improvement was seen. • the benefits of weekly physical activity held up regardless of what other heart disease risk factors they had. This is just one of many reports that Paffenbarger and others have published showing that regular exercise and daily physical activity can lower your risk of heart disease. Numerous clinical studies published over the span of several decades show that a poor aerobic fitness level is an independent risk factor for heart disease. This has been documented in men (Balady GJ, et al. 2004) (Lauer MS, et al. 1996) and in women (Gulati M, et al. 2003) (Mora S, et al. 2003). Research from the Cooper Institute in Dallas shows just how powerful aerobic exercise (aerobic fitness) is: • In 1998, researchers at the Cooper Institute reported that cardiovascular mortality decreased as aerobic fitness level increased in 25,000 men. This trend held true regardless of their cholesterol level (Farrell SW, et al. 1998). • In November 2012, a subsequent study from the Cooper Institute was published in Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. Nearly 41,000 men were monitored for an average of 17 years. The investigators found that high degrees of aerobic fitness substantially reduced the risk of death from coronary artery disease regardless of what a person's LDL-cholesterol level was. In fact, a person with an LDL-cholesterol of < 100 mg/dL but with a poor degree of aerobic fitness had a greater risk than a person with a very high LDL level of > 190 mg/dL and excellent aerobic fitness (Farrell SW, et al. 2012)! • Separately, Steven Blair, PED, a researcher at the University of South Carolina, analyzed data from over 50,000 patients studied at the Cooper Institute. He calculated how much each risk factor contributed to death in these patients. He concluded that "poor aerobic fitness level" is a greater contributor to the risk of cardiovascular death than are any of the traditional risk factors that clinical medicine currently monitors, eg., cholesterol levels, presence of diabetes or obesity, and even smoking. He found that poor aerobic fitness accounted for 16-17% of deaths whereas high cholesterol levels were responsible for only 2-4% (Blair SN. 2009). (In the graph below, aerobic fitness level is identified as "CRF": cardiorespiratory fitness.)  Calculating Heart Disease Risk: The "Risk Factor Gap" Recently, a "risk factor gap" has been identified when evaluating a person's risk for a heart attack (myocardial infarction). It turns out that relying on traditional health/disease markers such as cholesterol levels, blood pressure, etc. don't tell the whole story. • Researchers from Harvard monitored over 27,000 healthy women for an average of 11 years. They concluded that only 59% of the benefit of exercise (in reducing risk) could be explained by improvements in traditional risk factors....ie., a reduction in blood pressure, improvement in cholesterol, decreased insulin resistance, etc (Mora S, et al. 2007). Thus, in addition to its ability to improve "traditional" risk factors, this means that as much as 41% of the benefit of exercise is due to a direct effect, a very impressive level of impact! In other words, not only does exercise improve multiple risk factors simultaneously, but, also, exercise produces direct effects on coronary arteries, on various components of the blood, and provides numerous other beneficial actions. To achieve the same results with drug therapy would require 4 or 5 or 6 drugs. And, even then, you still wouldn't get all the health benefits that aerobic exercise provides! The American Heart Association had identified this "risk factor gap" phenomenon in an official white paper on the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease published in 2003 (Thompson PD, et al. 2003). In it, they stated: "In many studies, the lower frequency of CAD [in more physically active people] was independent of other known atherosclerotic risk factors." And, including specific measurements of aerobic fitness can dramatically improve the accuracy of common heart disease risk scoring systems such as the Framingham Risk Score (FRS) and the European risk scoring system "SCORE": • A 2011 evaluation based on more than 66,000 patients studied at the Cooper Institute ("Cooper Center Longitudinal Study") reported that, when a test of fitness level was added to the European risk scoring system, which evaluates risk for death due to cardiovascular disease, over 10% of the subjects required reclassification (Gupta S, et al. 2011). • When assessments of fitness level were incorporated into the widely-known Framingham Risk Score (FRS), in one study, nearly half of the subjects had to be reclassified from low or intermediate risk to high risk (Mora S, et al. 2005). Similar studies in women also showed that fitness assessments greatly enhanced the accuracy of the Framingham Risk Score (Gulati M, et al. 2003) (Mora S, et al. 2003). It now appears that aerobic fitness is far more critical in determining your risk of a heart attack than are any of the other risk factors regularly monitored. Here is a statement from researchers conducting the Cooper Center Longitudinal Study (CCLS) that provides a perspective on how risk of death decreases as fitness level improves: "A 55-year old man who requires 15 minutes to walk 1 mile is considered to have a low level of fitness. We would predict that his lifetime risk for death due to cardiovascular disease is nearly 30%. In contrast, a man able to run a mile in 10 minutes has a moderate degree of fitness and has an estimated lifetime risk of CVD mortality of just 10%." (Berry JD, et al. 2011). Thus, gauging the risk for coronary heart disease can be very misleading if the impact of exercise (aerobic fitness) is ignored. Poor aerobic fitness also helps to explain why heart disease can progress despite reducing the LDL-cholesterol value to very low levels with drug therapy. It is my opinion that these earlier determinations of heart disease risk based on cholesterol levels are flawed because they excluded "exercise" (or, even better, measurements of aerobic fitness) from the analysis (ie., the "risk factor gap"). Aerobic Exercise Reduces Coronary "Events" The epidemiologic research from the Cooper Institute showing that a person's state of aerobic fitness has a more dramatic impact than LDL-cholesterol on the risk of heart disease is powerful. But while these reports are impressive, they are still only a statistical analysis of risk. As mentioned above, what really matters is if coronary "events" (heart attacks) can actually be prevented with exercise. The results that Nathan Pritikin achieved by running and changing his diet (described above) is proof but that's just one example. Cardiac rehab programs have been shown to reduce the risk of a 2nd heart attack (Hamalainen H, et al. 1989) (Hedback B, et al. 1993). However, these programs are often conducted in a hospital or other controlled setting and generally involve not only exercise, but, also, a comprehensive approach to lifestyle modification, including counseling regarding diet, stress reduction, etc. The Lifestyle Program by Dean Ornish, MD, showed a much lower rate of cardiac events (compared to standard medical therapy) but, again, that is a comprehensive program involving not only exercise, but, also, diet modification, stress reduction, and smoking cessation (Ornish D, et al. 1998). So, what about exercise (ie., aerobic exercise) by itself? Does it really prevent coronary heart disease? Consider the following research studies where half the subjects exercised and the other half didn't: • Running (animal data): Monkeys were placed on an unhealthy, high-fat diet that produced a total cholesterol level of 620 mg/dL. Then, one group was exercised on a treadmill for 1 hour three times per week, while the other group remained sedentary. Coronary artery narrowing, coronary ischemia, and sudden death occurred in the sedentary group but not the exercise group (Kramsch DM, et al. 1981). • Stationary cycling (in patients with coronary artery disease after undergoing PCI): Italian researchers randomized patients who had just undergone a PCI procedure to either aerobic exercise or traditional treatment. The exercise program consisted of riding a stationary bicycle for 30 minutes at moderate intensity 3 times per week for 6 months. The group that exercised had a significantly reduced rate of progression of coronary disease and fewer cardiac events compared to the other group over the following 33 months (Belardinelli R, et al. 2001). • Stationary cycling (in patients with stable coronary artery disease): German researchers have published several studies showing that regular aerobic exercise achieves better results than PCI's. They randomized patients with stable coronary artery disease to either a PCI procedure, or, to aerobic exercise (riding a stationary bicycle 20 min/day, 6 days/week, at 70% maximum heart rate). Fewer cardiovascular events were seen in the exercise group after 12 months (Hambrecht R, et al. 2004) and after 24 months (Walther C, et al. 2008). • Walking (in older patients with no history of heart disease): Men and women 65 yrs and older who walked 4 hrs/week or more had a significantly reduced rate of being hospitalized for cardiovascular disease compared to those who walked only 1 hr/week or less (LaCroix AZ, et al. 1996). Thus, in a variety of different settings, aerobic exercise can reduce the occurrence of coronary "events" without the use of cholesterol-lowering drugs, or, diet modification. WHY IS AEROBIC EXERCISE SO EFFECTIVE IN CORONARY HEART DISEASE? So, regular aerobic exercise can prevent heart attacks because it improves a person's "cardiorespiratory fitness level," right? Yes, that's correct, but aerobic exercise possesses much broader benefits than just improving fitness level. As mentioned above, exercise is known to improve what are called "traditional" risk factors: ie., blood pressure, cholesterol levels, insulin resistance, and weight loss. This is impressive because no drug can modify all these risk factors simultaneously. But this only partially explains how and why aerobic forms of exercise are so effective in coronary artery disease. Regular aerobic exercise exerts numerous beneficial actions on the cardiovascular system. Explaining all the ways exercise is beneficial in heart disease would take another 10 pages so I will focus on blood flow: Aerobic Exercise Enhances Blood Flow "Cardiorespiratory fitness" reflects the body's overall ability to deliver and use oxygen. This, in turn, is largely determined by the vascular system, not the lungs. This is a supremely important concept because blood flow (oxygen delivery) is the most critical factor in the occurrence of heart attacks. I also believe that the "risk factor gap" described by researchers Blair, Green, Joyner, Moya and others exists because none of the risk factors that clinical medicine routinely monitors directly assesses blood flow (ie., oxygen delivery). Aerobic exercise can enhance both the structure (Shono N, et al. 2002) and function (Green DJ, et al. 2003) (Joyner MJ, et al. 2009) of blood vessels. The autopsy findings of runners Nathan Pritikin and Clarence DeMar are consistent with this. These changes in structure and function of blood vessels both dramatically affect blood flow. And, some changes can occur quickly: • Researchers from Switzerland showed that increases in blood flow occurred within 4 weeks of beginning a new exercise program in patients who had suffered a myocardial infarction. Subjects rode a stationary bike for 40 min/day, or performed resistance exercise, 4 times/week. Then, after another 4 weeks of no exercise, these beneficial changes were completely gone (Vona M, et al. 2009). However, in this study, blood flow was measured in the arm. What really matters is how well the coronary circulation delivers blood (oxygen) to the heart. Aerobic exercise enhances coronary blood flow in (at least) 2 ways: a) Increased coronary blood flow due to ENHANCED DILATING CAPACITY of coronary arteries: • In 1993, researchers from Stanford showed that the coronary arteries of marathon runners were more responsive (ie., greater dilating ability) than those in sedentary men (Haskell W, et al. 1993). • Subsequently, researchers from Switzerland showed that 5 months of aerobic exercise could improve the dilating capacity of coronary arteries even in people who are already reasonably fit. This study was very unique in that all subjects were cardiologists and underwent coronary angiography before and after the exercise program. These cardiologists engaged in running or cycling at least 4 days per week for at least 60 minutes per session. Coronary artery diameter (at rest), and, the ability of the coronary arteries to dilate, both increased significantly after 5 months. Also, these improvements in coronary blood flow occurred even though blood cholesterol levels did not change (Windecker W, et al. 2002). • German researchers showed that exercise-induced improvements in coronary artery blood flow can occur much sooner than 5 months: In a study of patients with stable coronary artery disease, riding a stationary bicycle 6 times per day for 10 minutes at a time (at an intensity of 80% of maximum HR) improved coronary blood flow after just 4 weeks. And this occurred even though there was no demonstrated regression of coronary lesion size (Hambrecht R, et al. 2000). b) Increased coronary blood flow due to PLAQUE REGRESSION: Regular aerobic exercise can also cause existing plaques in the walls of coronary arteries to regress. The case of Nathan Pritikin and the research of Dean Ornish, MD, et al. demonstrated that. (Keep in mind that these results were due to a combination of aerobic exercise with a very low-fat, low-cholesterol diet.) Aerobic exercise and cholesterol-lowering drugs like statins can each cause plaque size to shrink. While aerobic exercise can improve the ability of coronary arteries to dilate within days to weeks, a regression in plaque build-up in the walls of the arteries appears to occur much more slowly. The research from the German investigators mentioned above shows that riding a stationary bicycle for as little as 20 min/day can reverse coronary artery disease. Can preventing heart disease really be that simple? Yes it can. Aerobic exercise lowers the risk for heart disease even if: • No weight is lost (Manson JE, et al. 1999). • LDL-cholesterol levels don't change (Hambrecht R, et al. 2004) (Windecker W, et al. 2002). • Plaques in coronary arteries don't shrink (Hambrecht R, et al. 2000). EXERCISE RECOMMENDATIONS: Official Guidelines Current exercise recommendations for otherwise healthy adults are to perform moderate intensity aerobic exercise 150 minutes per week. (An example of "moderate intensity" aerobic exercise is brisk walking.) But this is just a general recommendation to maintain your health. Is this amount of exercise enough to prevent coronary artery disease? Yes. In 2011, public health experts from Harvard, Stanford, and the University of Texas reviewed 33 published research studies and concluded the following (Sattelmair J, et al. 2011):

AMOUNT OF

"MODERATE" INTENSITY

EXERCISE

PER WEEK | PERCENT REDUCTION

IN RISK OF

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE | | • 150 minutes/week | 14% reduction | | • 300 minutes/week | 20% reduction |

In other words, 150 min/week (ie., 30 min/day, 5 days/week) is acceptable, but 300 min/week is better. (It turns out that how "hard" you exercise is probably more important than how "long" you exercise....more on that below....) On November 12, 2013, the American College of Cardiology (ACC) and the American Heart Association (AHA) published their latest "Guidelines for Lifestyle Management to Reduce Cardiovascular Risk" (Eckel RH, et al. 2013). In this report, they recommend that people who have an elevated cholesterol level and/or elevated blood pressure perform aerobic exercise 40 min/day, on 3-4 days/week. The ACC and AHA committees included the findings from Harvard/Stanford/U. Texas researchers mentioned above in formulating this "official" recommendation. WHAT TYPE OF EXERCISE IS BEST? Aerobic types of exercise are best. Nathan Pritikin reversed his coronary artery disease with running (combined with diet modification). The researchers from Germany showed that riding an exercise bike can improve coronary circulation in people with heart disease. What about other types of exercise? A large Harvard study of male health care professionals shows how various types of exercise can lower the risk of coronary disease (Tanasescu M, et al. 2002):

| TYPE OF EXERCISE | AMOUNT | PERCENT REDUCTION

IN RISK OF

CORONARY ARTERY DISEASE | | • Running | 1 hr/week

or more | 42% reduction | | • Weight-training | 30 min/week

or more | 23% reduction | | • Rowing | 1 hr/week

or more | 18% reduction | | • Brisk walking | 30 min/day

or more | 18% reduction |

"Intensity" vs. "Duration" In the table above, note how much more effective running is compared to walking....even though running was only performed 1 hour per week! In other words, to decide if a particular activity is beneficial, duration and intensity both need to be considered. New research is now showing that, if your exercise sessions are really vigorous, then, you don't have to exercise as long (to decrease your risk of CAD). Exercise professionals call this "high-intensity training" (HIT) or "high-intensity interval training" (HIIT). A study from McMaster University in Canada published in the August 2013 issue of Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise showed that very short bursts of higher-intensity exercise were just as effective as prolonged lower-intensity exercise in patients with coronary artery disease: • Patients with documented CAD were randomized to 2 different exercise programs: One group rode a stationary bike for 1-min at an intense pace, followed by 1-min of rest. This was repeated for a total of 10 intervals. The other group rode at a more moderate intensity for 50 minutes/session. Exercise sessions were conducted twice per week for 12 weeks. The high-intensity, short bursts were just as effective in improving vascular function and aerobic fitness levels as the 50 minute sessions (Currie KD, et al. 2013). **WARNING**: If you have heart disease, you should not attempt any kind of intense exercise without first receiving medical clearance from your personal physician. And, even then, increase the intensity of your exercise sessions gradually.....ie., walk briskly for 2-4 weeks first, then consider increasing the intensity. At all times, it is wise to monitor your HR during your exercise session. Stop exercising immediately if you develop chest pain or pressure, pain radiating to your shoulder or down your arm, or, the sensation that you can't catch your breath. Walking to Prevent Coronary Artery Disease  Some of you might be surprised that something as simple as walking can be beneficial for a condition as serious as coronary artery disease. Many researchers have evaluated the impact of walking on coronary disease. It can be effective, but the results have been variable (Boone-Heinonen, et al. 2009). Why? Some of you might be surprised that something as simple as walking can be beneficial for a condition as serious as coronary artery disease. Many researchers have evaluated the impact of walking on coronary disease. It can be effective, but the results have been variable (Boone-Heinonen, et al. 2009). Why?

For walking to be effective, the key is to push the exercise heart rate up high enough. Does walking do that? It can. In one study, 142 patients with documented coronary artery disease were asked to walk 1-mile on a level surface as fast as they could. This exercise challenge pushed heart rate in all of the women and 90% of the men up to the target, which was 70% of their maximum (Quell KJ, et al. 2002). This shows that brisk walking does qualify as "aerobic exercise." The next question, then, is: if done regularly, can walking actually reduce the risk of heart disease? Yes. Researchers from UNC-Chapel Hill reviewed 21 published studies on the effectiveness of walking to prevent cardiovascular disease. They found that walking was beneficial, but it depends on how long you walk and how fast (Boone-Heinonen, et al. 2009). Several research studies provide some specific details: • The large-scale Women's Health Initiative Observational Study provided exercise and cardiovascular event data on nearly 74,000 postmenopausal women. The researchers found that brisk walking was just as effective as "vigorous exercise" in the ability to prevent cardiovascular events in these women. They concluded that "brisk walking for 3 or more hours per week could reduce the risk of coronary events in women by 30-40%." Further, the benefits of exercise were evident even in women who had a body-mass index (BMI) of 30 or higher (Manson JE, et al. 1999). • In the study of Harvard alumni, Paffenbarger and colleagues found that men who walked at least 3 miles per week had a 13% reduction in risk of developing coronary artery disease compared to men who walked less than that (Sesso HD, et al. 2000). • A study of British men with documented coronary artery disease who were followed for 5 years revealed that those who walked for at least 40 min/day had a lower death rate (Wannamethee SG, et al. 2000). • In the Harvard study of health care professionals summarized in the table above, it was found that walking was an acceptable activity for lowering risk of coronary disease, but ONLY IF it was done for 30 min/day every day, or, if walking was very brisk (Tanasescu M, et al. 2002). The good news is that substantial health benefits occur even if people exercise less than 150 minutes/week. Here is a quote from the Harvard/Stanford/Texas researchers (Sattelmair J, et al. 2011): "...the biggest bang for the buck for coronary heart disease risk reduction occurs at the lower end of the activity spectrum..." This means that you can see benefit almost immediately, even with small amounts of exercise. Whether you choose walking or some other activity (eg., bicycling, swimming, etc.), the key parameter is if it pushes your heart rate up high enough. For practical tips on making your walking effective, and to read more about the health benefits of walking, see: "Walking". MONITORING YOUR VASCULAR HEALTH So, let's say you've been walking and/or exercising regularly. How do you know if you've lowered your risk for having a heart attack? As discussed above, monitoring LDL cholesterol levels doesn't give the best assessment of your vascular health. Certainly, LDL-cholesterol helps to gauge risk, but it tells nothing about how well the vascular system is functioning. If blood flow (oxygen delivery) is the critical variable in coronary artery disease (and it is!), then how can that be measured? Health care professionals evaluate coronary blood flow (oxygen delivery) with a test called the "exercise EKG." During this test, the patient walks or runs on a treadmill, or rides a stationary bicycle, while being monitored with an EKG. Poor blood flow through the coronary arteries shows up on the EKG tracing. However, measurements of exercise capacity and how quickly your heart rate decreases right after exercise stops ("heart rate recovery") are better predictors of risk (Greenland P, et al. 2010). Exercise physiologists assess aerobic fitness (exercise capacity) by measuring your "VO2max". This test also requires running on a treadmill. During this test, you are breathing through a snorkel and you must run hard. While both of these tests are useful, they're complicated, cost time and money, and, just don't qualify as a simple screening test....which is what people need. It turns out you can assess the health of your vascular system without the need for a complicated medical or laboratory test: Resting Heart Rate: Aerobic fitness is critical in reducing your risk of a heart attack. Numerous research studies show that, as aerobic fitness level improves, the risk of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality decreases. And, as your aerobic fitness improves, your resting HR will slow down. This is good! So, resting HR mimics your level of aerobic fitness. But, does it provide an indication of your vascular health? Yes, according to Paolo Palatini, MD: "More than 50 articles have been published on the significance of elevated HR......all but 2 reported an association between fast HR and all-cause mortality in men." (Palatini P, 2009). (NOTE: the first study to focus attention on this was published in 1945!) Here are several examples: • Over 5700 men in France were followed for 23 years. It was found that men with a resting HR of 75 or higher had a 3.5-fold increased risk of sudden death compared to men with a resting HR of 60 or less (Jouven X, et al. 2005). • Men and women in Norway who had a resting HR of 70 or lower during their first assessment, but, had a resting HR of 85 or higher 12 years later, had a nearly 2-fold increased risk of death from coronary artery disease (Nauman J, et al. 2011). Still, one lingering question remains: does an elevated resting HR simply represent poor aerobic fitness, or, can resting HR be relied upon as an independent measurement of heart disease? This is a subtle but important distinction because aerobic fitness is more difficult to measure, whereas anyone can obtain their resting HR. • In April 2013, researchers from Denmark answered this question. They evaluated nearly 3000 men with no history of cardiovascular disease and monitored them for 16 years. They found that, indeed, an elevated resting HR was an independent risk factor for death (Jensen MT, et al. 2013). This means that your resting HR is something you should measure on a regular basis. Here's how to do it: The best time to check your resting HR is right when you wake up. - The night before: do not drink any alcohol; put a clock or watch next to your bed.

- As soon as you awake, before even sitting up, take your pulse. This can be done by placing 2 fingers on the side of your throat or on the back of your wrist.

- Count your pulse for 15 seconds and multiply by 4.

- Goal: a resting HR of 70 bpm or less.